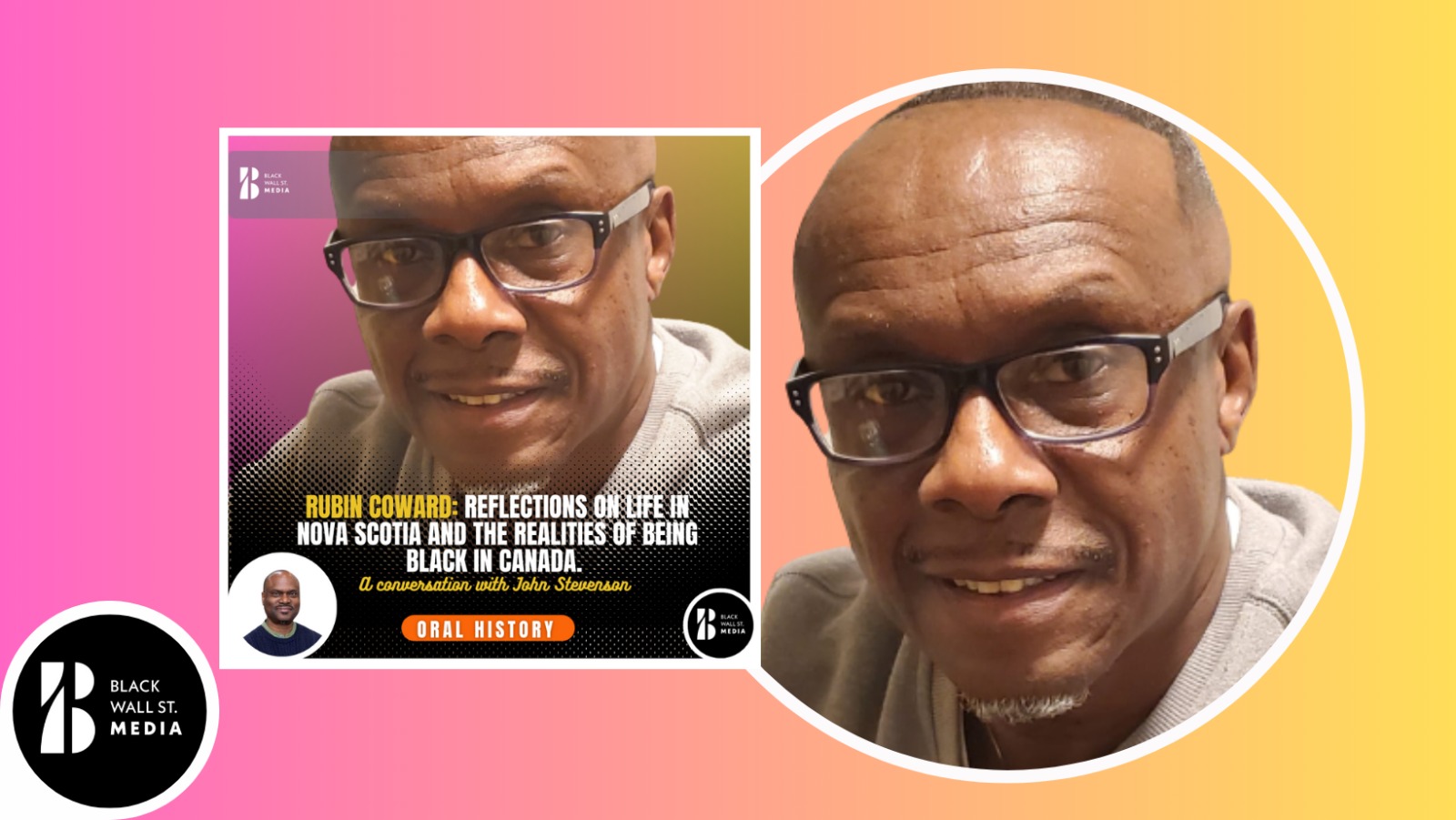

Oral History

From Barbados to Nova Scotia: The Journey of Arthur Reginald Coward.

“"Education is our rod and our staff; the secret is to not ask for what you know an oppressive people don’t want to give. We must take it. We are what we think, and we must think and act like the Kings and Queens they stole from Africa." - Rubin Coward.”

Black Wall St. MediaContributor

Rubin Coward: Reflections on life in Nova Scotia and the realities of being Black in Canada A conversation with John Stevenson

This article provides an in-depth look into the life of Rubin Coward, his familial legacy, and the broader experience of Black Nova Scotians. It addresses the history, challenges, and triumphs of this community.

The article delves deep into the heart of racism and how Black communities have resisted and survived such adversities in Canada.

Coward’s insights and life experiences serve as an example of resilience and dedication to preserving one’s culture and combating systemic racism.

This conversation with John Stevenson not only honors Rubin Coward and his father’s legacy but also educates readers on the rich tapestry of Black history in Nova Scotia. It serves as an important reminder of the contributions, struggles, and indomitable spirit of Black Canadians.

Historians looking at the place of Black people in Nova Scotia consider immigration to the area falling into four broad categories:

1.The arrival of Black loyalists (and Black slaves brought by white loyalists as part of their slaveholdings in the year following the American Revolution of 1776);

2.The relocation of Jamaican maroons in 1796;

3.The influx of Black refugees from the War of 1812;

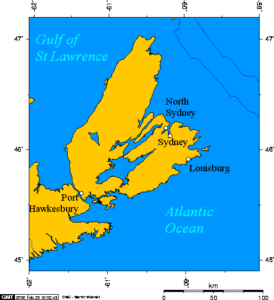

4.The arrival of Black workers and their families from the islands of the Caribbean to work in the coal and steel industry in towns such as Sydney and Newbury in Cape Breton island, in the first two decades of the 20th Century.

Indeed, the migration of Caribbean labour to Sydney, Nova Scotia in the early 1900s created a culturally distinct community in North America.

It is against this fascinating background that we consider the story of Rubin Coward, a social change advocate and former non-commissioned officer in the Canadian Air Force, who was born in Nova Scotia almost 67 years ago.

Rubin’s trailblazing father, Arthur Reginald Coward, was born in St Andrew, Barbados, in 1890.

He emigrated to Nova Scotia in 1912 via Panama, after working on the Canal. Rubin recently spoke to Black Wall Street’s John Stevenson.

Here is his fascinating story!

John Stevenson: How did your father Arthur Reginald Coward come to live in Nova Scotia from Barbados?

Rubin Coward: My father, Arthur Reginald Coward, born to William Coward and Emily Francis Harris, was born on 3 February, 1890 in St. Andrew, Barbados in a place called The Swans.

Prior to 1834 (the abolition of the Slave Trade) the Swans was a Sugar Plantation in which Blacks were brought from Africa as Slaves.

Our father, the last of 10 children, completed Standard 8 (which is the equivalent to grade 12 in Nova Scotia, senior matriculation); and, in 1911 went to work on the Panama Canal, where he contracted Malaria.

In conversations with my father, he indicated that on return to Barbados in 1912, he had decided that he was going to Venezuela; however, the Ticket Master instructed him to pursue meaningful work in Sydney, Nova Scotia, Canada.

The rationale expressed by the Ticket Master was that dad didn’t have a command of the Spanish language, and that his solid education would place him at the top for employment in a budding Steel Plant in Sydney, Nova Scotia that was conceived by an American businessman named Henry Whitney – hence the name of our community was his name’s sake – Whitney Pier.

My dad worked there from 1912 – 1917 (when he started he was making 17 ½ cents an hour). He confided that a $20 dollar bill was as rare as hen’s teeth.

In 1917, his boss instructed him to train three Europeans (White People – wherein his boss could hardly speak English).

When my dad inquired as to why he was training them, the response was that they would be over him.

Dad’s response was: “I’m going home to take a bath, and when I return have my cheque ready – I quit!”

Let’s say this transpired on a Tuesday, and by Friday when the whistle blew, which connoted an accident – the billets these three men had piled up had let go, come down and killed all three of them.

My father had expressed deep regret for the unfortunate deaths of the three men, but conveyed to me that that was the price his supervisor had to pay for the needless racism demonstrated towards him, merely because he was Black.

This was the first-time dad had talked to me as a boy about how nefarious racism was, and the consequences associated with this vile practice.

Dad started a farm amongst other interests like teaching himself to read, write, arrange and play the piano and saxophone (only classical and gospel music was allowed in our home).

He taught all of my siblings from his first marriage, but only Reg and I from the second marriage.

My eldest brother, Alfred Coward, commented in his Foreword entitled: The Settlement & Legacies of West Indians of Cape Breton Island, on how he experienced our Dad: “Arthur Coward, indulged in education at home by way of correspondence courses … English, Rhetoric, Writing, Oratorical, etc., and that this ritual continued for a number of years after working at the Dominion Iron and Steel Company prior to conducting his own business a few years later.”

In fact, our father was an “entrepreneur” long before I had any idea of exactly what the word meant.

JS: How significant is Nova Scotia to Caribbean communities? Why did they move to this part of North America in the first place? ∙

RC: The importance and significance of Nova Scotia to Caribbean communities signaled that they could pursue meaningful and gainful employment, where their higher education was favored and admired.

And with that stated, Caribbean people flocked to Nova Scotia en masse, armed with the information that their education and they would be valued in this nascent workforce.

It signalled an opportunity to be treated as equals with dignity and respect.

JS: What aspects of Barbadian culture and heritage did you and your siblings receive from your parents?

RC: Chief amongst the various aspects of Barbadian culture and heritage, our parents instilled in us a desire to pursue higher education and to always demonstrate respect toward all of the elders in the community.

A failure to carry out the latter would most definitely result in a beating from our parents and most likely from those we failed to speak to or address respectfully.

For example, Good Morning Mr. Best etc., because if you call him by his first name – Ronald, “breakdancing” was practiced long before it became popular – we would get the beating of our lives!

We were encouraged to be disciplined in playing the piano – practice was required daily (for approximately one hour), and if you failed to practice, a beating was the reward. And, I received many. Not because I wasn’t disciplined, but rather, whenever I would make a mistake, a rap on the hands with a ruler was my signal to get it “right”.

What was most interesting, however, whenever dad made a mistake, I took note that he didn’t beat his fingers or hands?

From Barbados to Nova Scotia

Marcus Garvey had a profound impact on

the Black Communities of Nova Scotia.

JS: Members of your family have distinguished themselves in Canada with many accomplishments – entrepreneurship, military, educational, music, social advocacy, etc. Were you all encouraged to blaze these trails? Was there a sense of mission to be accomplished in this manner?

RC: Almost all of my siblings from both of our dad’s families (because I and five other siblings are from our dad’s second marriage to our mom Sybil Coward nee Francis) valued education, excelling and emerged from a discipline that encouraged us to succeed.

Not because our dad or mom specifically said so, we just understood that they always wanted us to do our very best in whatever we engaged. For example, if I asked my dad a word, I wasn’t familiar with, and asked him for the meaning, his response would invariably be: the Funk & Wagnalls Dictionary is there – “look it up!”

Needless to say, there was a lesson in his wise instruction to “look it up” – that way I never forgot a word I had to look up; and, this compelled me to always look new words up instead of being told to do so.

I recognized that our dad admired astuteness, and I endeavored to be just that – astute and erudite.

Moreover, my dad had confided in me that in 1930 when Marcus Garvey came to Sydney with the “Back to Africa Movement Speech”, he was chosen as one of the delegates who would escort Mr Garvey between Sydney and Glace Bay where he gave speeches.

Equally as important, however, my dad had schooled me in the positive history and achievements of Black men like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, Haile Selassie, Emperor of Ethiopia, and said to be a descendant of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba.

He told me I would have to work twice as hard as my European counterparts, so move forward “always doing your very best.

Black people in Nova Scotia have been the targeted group along with our Indigenous brothers and sisters for Racial Profiling, Anti-Black and Anti-Indigenous Racism, that have regrettably taken a significant toll on the overall mental and physical health of our peoples.

These Racially charged and unsolicited attacks have resulted in the continuation of “Intergenerational Trauma” that correlate into such things as high blood pressure, depression, anxiety, stress, low self-esteem, a glass ceiling in employment, and in large measure, a significant exodus of the descendants of Barbadians in Sydney, leaving to seek employment in such other places like Toronto, Montreal, Calgary and Vancouver. Essentially,

Racism has driven us out. In fact, in the early 1970’s, my oldest sister Clotilda was the driving force to establish a committee to address poor housing, the lack of a nursing facility in Cape Breton, employment etc.

I am extremely proud to share that we (and Clotilda’s children) staged an event, ‘Celebrating the Life and Legacy of Dr. Clotilda Douglas-Coward-Yakimchuk (1932 – 2021)’ hosted by Cape Breton University 13 April, 2023, in her honour.

JS: Why do Black diaspora communities outside Canada know so little about the history of African-descended people in Nova Scotia – and Canada more generally?

RC: I believe that very little is known about the struggles of Nova Scotian Blacks, indeed, Canadian Blacks because the media is Racist.

They are “always” ready and willing to report on anything negative, but remain mute when we are on the move in a very positive and proactive manner.

Why? The Cognitive Dissonance that brother Frantz Fanon describes that it occurs when “people hold a core belief that is vey strong [and] when they are presented with evidence that works against that belief, the new evidence cannot be accepted [so] they will rationalize, ignore or even deny anything that doesn’t fit with that core belief.

JS: What is the future looking like for Black folk in Nova Scotia?

RC: Quite frankly, I am extremely optimistic about the future for Black and Indigenous Nova Scotians.

We are like Uncle Charles Wilson (the singer) says, “In it to win it, not turning around, won’t let anybody turn us around.”

God/the Creator and the ancestors walk with us now, education is our rod and our staff, the secret is to not ask for what you know an oppressive people don’t want to give.

We must take it. We are what we think, and we must think and act like the Kings and Queens they stole from Africa. As brother, Barack Obama once commented: “Yes we Can!”

And as brother, Nelson Mandela provided us by his sagacious leadership and the wise precepts from that African Proverb: “A single twig is easily broken,but sticks in a bundle are indeed very hard to break!”

Therefore, let us be those sticks in a bundle and practice the true spirit of Ubuntu (an individual becomes a person through other people or his or her community)

JS: What kinds of organisations and strategies have you and others had to adopt in order to preserve your culture and combat racism?

RC: In Nova Scotia we have engaged in very meaningful endeavors to proactively change the landscape and how we as a people are viewed.

The Black Report was a report prepared in 1994 consisting of 3 volumes and 467 pages that clearly underscored the disparities in Education and Early Childhood Development for Black Learners in Nova Scotia.

In 1995 I wrote a proposal for a Community Development Worker and an Assistant. At this time, I was volunteering to assist Black Learners in the communities of Lucasville and Upper Hammonds Plains. Two Black communities that were left behind.

In fact, the proposal written identified there is a need to have Development Workers in the 52 Historical Black Communities here.

I proposed $45,000 per/year for the Development Coordinator and $26,500 per/year for the Assistant.

This was accepted and adopted by then Human Resources Development Center (HRDC) manager, Keith Cameron of Bedford, Nova Scotia.

Regrettably, the various communities failed to solidify a comprehensive Strategic Plan, and they were all closed in February of 2014.

In central Nova Scotia, we have a group of proactive brothers called the Brotherhood.

They are instrumental in accessing a plethora of services for Black men and women like, Psychological Services, Psychiatric Services, Social Services, Lawyers inter alia.

They are doing some wonderful work here, and they are lending a hand to establish a similar group that I believe will be called the Sisterhood.

Some 30 years ago I began as a Community Advocate, borne out of the Racism I was targeted for as a Senior Non-Commissioned Officer in the Canadian Air Force.

I suffered some three years of blatant Anti-Black Racism as the Chief Clerk, while attempting to perform my duties at 404 Maritime Patrol and Training Squadron, 14 Wing, Greenwood, Nova Scotia 1990 -1993.

I was Clinically Diagnosed by my angel, Mr. John Manning, a Black Clinical Counseling Therapist, who diagnosed me with PTSD from the Racially charged attacks I endured while at 404.

Our eldest son developed bipolar disorder, and we “all” underwent Clinical Counseling Therapy with Mr. Manning and enjoyed the support from his family.

JS: How have your own encounters with racism influenced your work within the community?

RC: The Racism I faced was so traumatic that once Mr. Manning identified my malady, he instructed me to do what I needed to do to regain the confidence, courage, self-esteem that those bandits worked indefatigably to destroy in me, simply because I was Black, very competent, and “in charge!”

Consequently, I continued to study jurisprudence – The Supreme Court of Canada, The Dominion Law Recorder, Quebec Law, Ontario Human Right Commission decisions, The Canadian Human Rights Decisions, Nova Scotia Human Rights Decisions, Quick Law which was a data base for law students studying at Dalhousie Law School, located in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Subsequently, I began to represent victims from the Police Departments, RCMP, Military Members, Seniors that were ripped of by unscrupulous Contractors – those that suffered the following: Sexual Assault, Racism, Discrimination as per the Code, with the Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission,

The Canadian Human Rights Commissions, The Women’s Prison in Truro, Nova Scotia, and writing Legal Briefs and winning against Law Firms from Toronto like Hicks/Morley who sent a senior partner to battle me, and we won significantly. Sysco Halifax, I battled with over Racism in the workplace and won.

Many others, I emerged victorious over seasoned lawyers. The ancestors walked with me as I emerged victorious in a Racism case I traveled to Toronto for (in February of 2023) to assist a lady I grew up with in Sydney, and again, we won.

And, as a Principle Plaintiff in a Class Action Lawsuit three other colleagues and I filed and began on the 14 of December ( a battle I’d been fighting for over 31 years), 2016 against the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) for Systemic Racism, Institutional Discrimination against Racially Visible People and Indigenous People, we are pleased to announce that we achieved a Settlement Agreement In Principle (AIG) on the 19th of August, 2019 with the Department of Justice (DOJ), and have proposed Systemic and institutional Changes within the framework of CAF.

We are extremely optimistic going forward that for future generations, we may be able to achieve the improbable – that young people will “never again” have to endure from the bandits within, the horrible experiences we were targeted for and subjected to, simply because we are Black or indigenous.

JS: What unique experiences can Black Nova Scotians offer to communities of colour in the UK, for instance?

RC: We love our brothers and sisters in the UK, and we know we possess the gift inside to emerge victorious.

We and our brothers of the UK must walk together for the common goals they wish to achieve.

We and our brothers and sisters of the UK must break the shackles of the mind that William Lynch spoke about in Virginia almost three hundred years ago on how to keep us hating and not respecting each other.

This my friend, is the way forward. Believe in yourselves and believe and love each other, because, yes we can!

Plaintiff in class-action lawsuit against Canadian Armed Forces ‘extremely optimistic’ about outcome

John StevensonContributor