HEALTH

The Mother’s of Gynaecology Were Black Women

“So Why Are We Still So Misunderstood?”

Daniella MaisonEDITOR OF SOCIAL CAUSE ISSUES

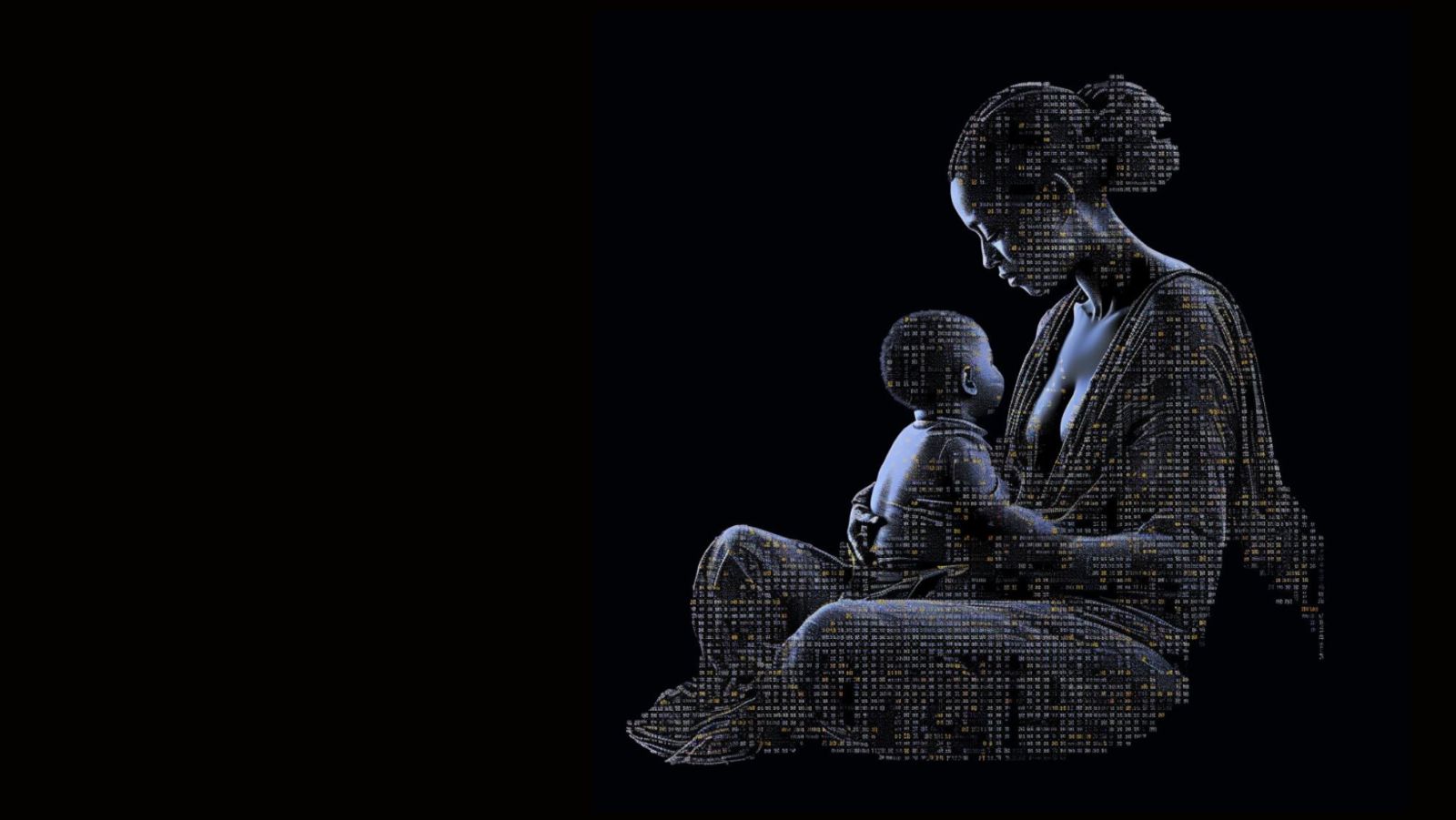

Blessing of becoming a mother

Last month, I was overjoyed to experience the blessing of becoming a mother when I gave birth to my son.

The nine months that preceded this occasion were, for the large part, joyous.

Aside from the days I spent loading up on chlorophyll and meditation, one of greatest satisfactions (and mental challenges) was defying the doctors who at every turn reminded me I was more likely to experience a myriad of ailments (none of which I had).

At this point most of us have likely seen the staggering statistics around the reality of childbirth for Black women in this country.

Black women in the UK are five times more than likely to die in labour than their white counterparts;

Black pregnant women are eight times more likely to be admitted to hospital with COVID-19 and Black babies have a 121% increased risk of being stillborn, with a 50% increased risk of dying within 28 days of birth, when compared with white babies.

I found myself protesting to no avail as white healthcare professionals depicted my ‘BAME likelihoods’ that such a generic term couldn’t possibly envelope my personal specifics.

It was a small victory to prove them wrong at each test and turn. It was also traumatic.

Thankfully I had the guidance of formidable doula, Anisa Abdullah who had prepped me well for what I might encounter as a ‘BAME’ female, but I’ll be the first to admit I underestimated the mental process of feeling continuously ‘less than’.

On numerous occasions during my pregnancy I was told that I was more likely to die in childbirth or give birth to a stillborn baby and as the process went on I started to feel like an alien.

These details are presented as ‘statistical facts’ but feel far more like micro aggressions.

I met several wonderful midwives who were supportive and reassuring; but I also met with several who constantly referenced my ethnicity as though it was my Achilles heel; as though my so-called ‘BAME’ body (which was never referenced as a positive attribute) couldn’t be understood or believed in; that it would ultimately let me down and fail me.

THE ISSUE

The statistics aren’t conspiratorial; they are accurate.

The issue is that they are entirely preventable. Black women aren’t more likely to die in childbirth because we are Black; our melanin isn’t the issue, our perception is.

Simply put, we are more likely to die in childbirth because we are undervalued. We are not monitored as carefully as our white counterparts are. When we do present with symptoms, we are dismissed.

It’s not even just a matter of money, which was proven when super-athlete Serena Williams was ignored when she reported symptoms of a near-fatal blood clot to nurses after the birth of her daughter.

As the proud daughter of a nurse, I have enormous respect for the NHS, which I believe is still a privilege. It is also a microcosm of our society wherein the same inequalities are at play.

It is the harsh reality that exposes the vulnerability of Black people in U.K. healthcare systems, where implicit bias insidiously permeates the healthcare workforce and puts the lives of Black women at risk.

Black women’s cries for help are unheard, unseen, and misunderstood. As a result of this, we are disproportionately suffering in an the very industry that our bodies helped to shape.

Now at home with a bouncing 8lb baby boy, and in the heart of Women’s History Month, I felt I had to write a piece that acknowledged that as black and brown women, we should never feel that our bodies are other. We should never tolerate being treated as though our bodies are an anomaly.

The largely unknown fact is, Black women are the very reason that gynaecology as we know it exists today. Our black bodies are the prototype on which genealogical advancements were cultivated.

Our genetics wove the original tapestry of weft threads that is now modern obstetrics and genealogy. Our bodies were sacrificed on the altar of scientific development; our minds contributed to their advancement.

Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave, I am the dream and the hope of the slave. I rise.

The field of gynecology was pioneered by 19th century men and as such it was deeply intertwined with slavery.

“father of modern gynecology.”

In America, there are no less than three separate statues in the U.S.A honoring Dr. James Marion Sims, hailed as the “father of modern gynecology.”

Still, little recognition is given to the three known (out of 11 total) black slave women he exploited through nonconsensual and anaesthetic-free surgical experimentation.

On a summers day in June of 1845, Anarcha had been in agonising labor for 72 hours when Dr. J. Marion Sims went to her bedside to assist her on the Westscott Plantation located in Montgomery, Alabama.

It wasn’t to be her last encounter with Dr Sims. Her infected wounds and fistulas garnered Sims’ interest in using her for experimental surgery, as fistulas were common among slave women due to their malnutrition.

It took Dr Sims 30 anesthetic-free operations before he successfully closed Anarcha’s fistula and tears.

Teenagers Betsy and Lucy are a similar story, as were the other 11 enslaved women left in his care by their slave owners after he ‘leased’ their bodies in the name of science.

Between 1845 and 1849, Dr. Sims meticulously documented how he perfected his gynaecological procedures at the (excruciating) expense of the girls.

Without their sacrifices women who now suffer post-birth vaginal tears wouldn’t be routinely mended. Sims invented the vaginal speculum, a tool used for dilation and examination that is used in modern PAP smears.

He also pioneered a surgical technique to repair vesicovaginal fistula, a common 19th-century complication of childbirth in which a tear between the uterus and bladder caused constant pain and urine leakage.

Yet, history hasn’t recorded the voices of the women who made these advancements possible.

These are our forgotten Mothers of Gynaecology.

Of the many carefully crafted stereotypes that scientists, physicians and slave owners perpetuated, a key one was that African Americans could not feel pain, and therefore they could justify their treatment of Black women and men for medical research.

Black women still grapple with persistent medical racism

Today, black women still grapple with persistent medical racism and the ongoing health disparities that result from systemic discrimination.

This is especially true for black mothers, whose maternal mortality rate remains a gargantuan three and a half than that of their white counterparts, largely because our pain is overlooked and our symptoms disbelieved.

This information is still being passed down. All these many years later and our medical system still continues to teach that Black women experience pain differently than white women.

A survey from campaigning organisation Five Times More has found that Black women in the UK continue to experience discrimination and are receiving a mixed level of maternity care during the antenatal, labour, and postnatal period.

It is not only our suffering that has shaped gynaecology but our intellect. Something else we aren’t taught in school is that Mary Beatrice Davidson Kenner graduated high school in 1931 and started college at the prestigious Historically Black College and University (HBCU) Howard University.

She was unable to finish due to financial pressures but whilst working as a federal employee, she saved enough money to file her first patent ever for an adjustable sanitary belt with an inbuilt, moisture-proof napkin pocket in 1957. At the time, women still predominantly relied on scrap cloth and rags to absorb their menstrual blood and would have continued to for longer were it not for her wondrous mind.

As women continue to speak out in their droves on their birthing experiences and the multitude of micro aggressions, macro aggressions, oversights, assumptions and lack of understanding surrounding them, we need this issue to be addressed now more than ever.

Interventions that redesign obstetric care and centre Black female needs are imperative to mitigate the glaring disparities and equalise the birthing field.

More than just equality, as black women we have the right to feel empowered and the quickest way to empowerment is via knowledge.

The positive, peaceful power that comes from knowledge, understanding, and realisation that we too are originators and influencers in areas where we feel mislaid and displaced.

Last year, Anarcha, Lucy and Betsy were honoured with three statues acknowledging the suffering of bondswomen overshadowed by the white doctor who operated on them without their consent.

The next step should be to include them in biology lessons and the history books of scientific advancements.

Race may be a social construct but it has a profound impact on the lived experiences of black and brown people at multiple levels and obstetrics and gynaecology are not exempt.

So much tangible graft needs to be done to change the pervasive and inequitable systems that lead to poor birth outcomes and it starts here and now, by the healthcare industry recognizing and embracing us.

We who proudly stand upon the shoulders of the Mothers of Gynaecology. Anarcha. Betsy. Lucy. #SayTheirNames.

Black Wall St. MediaContributor