HEALTH

Beyond The Barrel

“Addressing the Impact of Parental Migration on 'Barrel Children”

by CHJ Fellow Melissa NoelContributor

What does it mean to build community around an issue?

What does it mean to build community around an issue?

This is the question I asked myself over and over as I explored the long-term emotional and psychological impact of parental separation due to migration on the Caribbean’s “barrel children” and their families, both in the region and in the United States.

When I started my reporting on this issue over a year ago, I knew that I wanted the stories I did to actively involve the community they were about, as well as serve as a catalyst for further change in a community where discussions of mental health issues are often considered taboo.

Barrel children are the children left behind in the care of relatives or friends when parents migrate to other countries for work.

They receive material goods via shipping barrels as well as money, but they often lack emotional nurturing from their parents.

As a Caribbean-American, the brown cardboard or blue plastic barrels have always been a familiar sight.

It’s a typical and cost effective way for so many families (including my own) to send things like food, clothing and other items to loved ones in the region.

Once a barrel reaches its destination and the contents taken out, it is often repurposed as a storage unit, used to catch rainwater or halved and turned into kitchen gardens.

I always thought of the positive things these barrels represented — love, care, support.

That changed in early 2016 when I attended a Caribbean Film Academy screening of the short film “Auntie” in Brooklyn.

The fictional film presented some of the very real ways migration affects the lives of those left behind.

After the screening I met a woman from Trinidad and Tobago who told me that her childhood separation from her mother still negatively affected her as well as their relationship 20 years later.

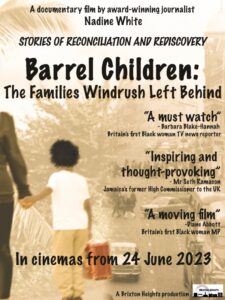

Barrel Children: The Families Windrush Left Behind documentary trailer

The Windrush generation saw people answer the call of ‘the mother country’ to help rebuild Britain in the 1940s and 1950s.

The story of Windrush has come into painfully sharp focus but what is less well-known is the story of the children of Windrush; those whose parents left for Britain and who they only knew of through the ‘barrel’ care packages sent back to the Caribbean.

This is their story, told to Nadine White, of growing up away from their parents before being ‘sent for’ and finding themselves in a world that made little sense to them.

I knew immediately that I needed to look into this further.

Generally, migration from the Caribbean region is viewed as a development issue, with positive economic effects since cash remittances from abroad are a valuable source of income for many households across the region.

I instead reported on is the negative impact migration can have on families, particularly the well-being and mental health of children, who are often separated from their parents for five or more years.

I interviewed more than 30 children, teachers, mental health professionals, parents and others in Jamaica, Miami and New York City — home to the largest Caribbean diaspora, and one of the largest Jamaican ones, in the United States — about the complexities of parental migration, the long-term psychological impact it can have, and the difficulties parents and children face when reuniting after years of separation.

I felt it was important to report on the issue from the perspective of children currently separated from parents who have migrated as well as those who have reunited in the United States after many years.

Parents make a difficult decision to leave their children behind and migrate to another county.

They want to provide more for their families. It is often done with the best of intentions, but there are consequences.

Although barrel children may receive money and goods, they often lack the emotional support they need from their parents.

I felt it was important to report on the issue from the perspective of children currently separated from parents who have migrated as well as those who have reunited in the United States after many years.

Parents make a difficult decision to leave their children behind and migrate to another county.

They want to provide more for their families. It is often done with the best of intentions, but there are consequences.

Although barrel children may receive money and goods, they often lack the emotional support they need from their parents.

Mental health professionals say this can lead to low self-esteem, depression and feelings of abandonment. These feelings, they say, can lead to behavioral problems and poor academic performance. Some children are also left vulnerable to physical or sexual abuse and are predisposed to risky behaviors.

Even when reunited with their parents, they face difficulties in repairing the bonds damaged by separation. Not all of these stories have unhappy endings, as many families have navigated the separation and maintained their bonds.

In my reporting I did my best to show that there’s a wide range of experiences, as well as ways to mitigate the emotional impact of separation with proper planning.

My community engagement training enabled me to create “Beyond The Barrel: Sharing Our Stories of Migration and Separation,” a film screening and panel discussion on parental migration and its impact on Caribbean families.

For the event, I partnered with The Barrel Stories Project, Museum Hue and the Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute in Harlem to bring together parents and children once separated by migration, social workers that counsel these families, as well as creative types and community members who sought to use their platforms to advocate for expanded community programming and policy changes.

As several Caribbean social workers told me, they saw a need to bring families, teachers, mental health professionals and organizations out of their silos and have them work together to bring about both cultural and community changes.

In other words, this community wanted to move from conversation to action on this issue. The purpose of “Beyond The Barrel” was to expand the conversation about the effects of this common but rarely discussed issue in Caribbean communities.

It will now be turned into an event series and brought to other cities throughout the U.S. and Canada with sizable Caribbean diaspora communities.

Here are some tips for reporters covering migration and mental health impact:

Mental health is a taboo topic for many Caribbean communities. Understand that a gentle approach to children and their parents is necessary, no matter the age or how long ago the separation was.

‘Barrel Children: The Families Windrush Left Behind’, my first feature-length documentary, will be showing at selected UK cinemas between Saturday 24 June & Wednesday 28 June 2023.

Interview professionals who can explain to the long-term impact of separation on attachment and bonding, particularly during childhood years.

Understand the cultural attitudes toward migration and present various outcomes, both positive and negative.

Know that a considerable amount of time gaining will be spent gaining the trust of potential sources.

There is often a lot of shame when talking about this. Seek out social workers, community organizations and advocates who can help you facilitate connections and give you more credibility among impacted families.

There is a lot of fear in these communities about discussing immigration issues and experiences.

The actions of the current U.S. president have heightened those fears.

Be mindful, be cautious and be upfront about wanting to highlight the mental health impact, not their immigration status. Finding specific numbers on “barrel children” will be difficult.

Instead, you’ll need to rely on metrics such as the number of people who have migrated from a particular country or region over a period of time. You can still get across the extent of the issue this way.

Although this is an underreported issue, it’s not a new one. Avoid sensationalizing it as such.

Seek out what’s improving in the region and in the diaspora communities and be sure to include in your stories. Partner with organizations and seek out additional community platforms to extend the reach of your project.

by CHJ Fellow Melissa NoelContributor