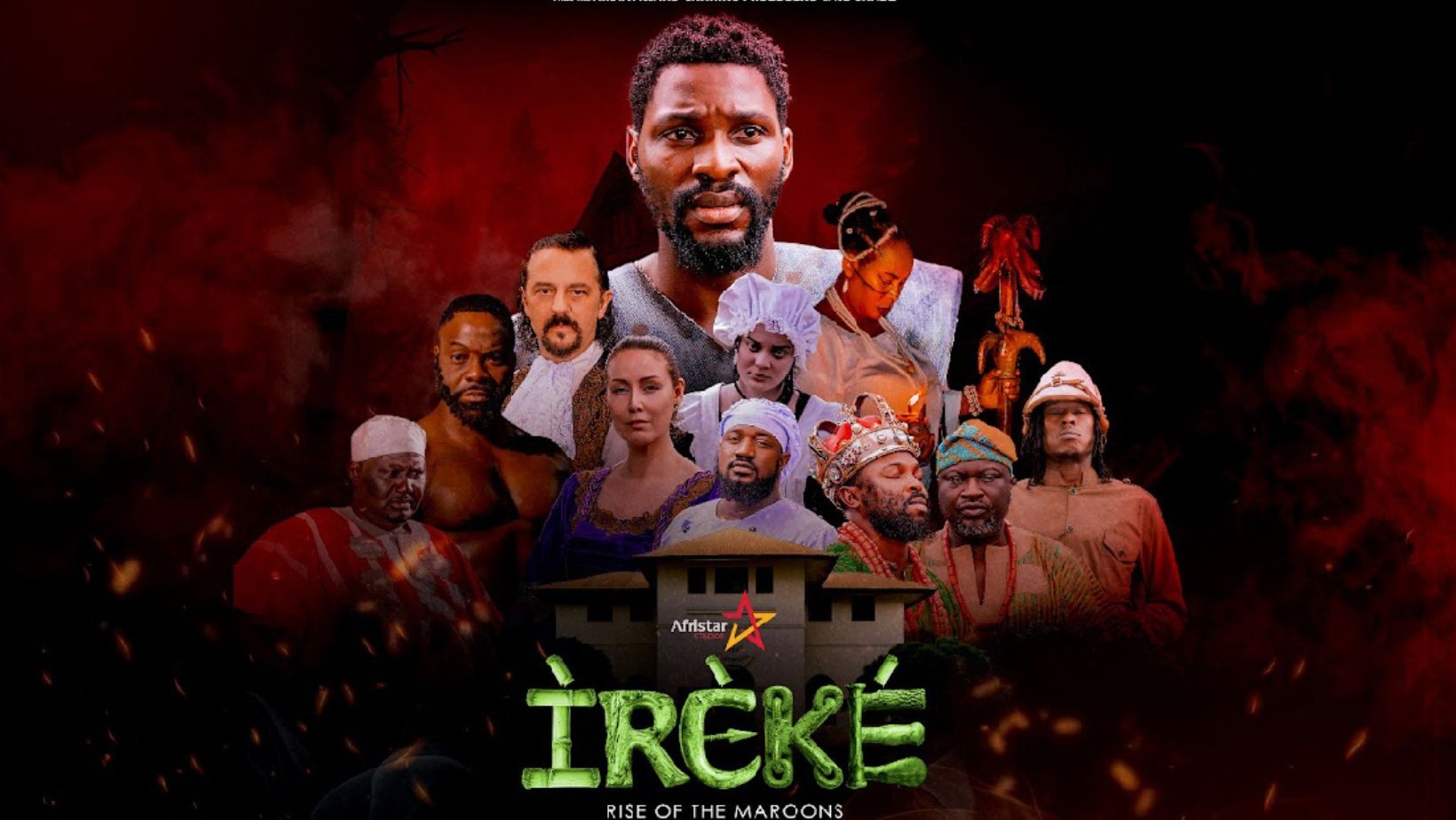

Reviewed by Black Wall St Media

Ireke: Rise of the Maroons (2025)

“★★★★★

This is not just a film. It is a hymn for the defiant. A mirror for the forgotten. A roar for the silenced.See it. Share it. Remember.”

BWSMCONTRIBUTOR

Some films are made to entertain.

Some are made to educate.

But every once in a while, a film is made to remember — and to refuse forgetting.

“Ireke: Rise of the Maroons” is one such film.

Directed with haunting precision by Emmy-nominated Gbolahan Peter Macjob, Ireke is a cinematic reckoning. It is both an elegy and an uprising — a storm of memory and myth, rooted in the brutal soil of colonial Jamaica and royal West Africa. This is not a film you merely watch. You endure it. You listen to it. You survive it.

At the heart of this 96-minute epic is Prince Atanda, played with raw vulnerability by Tobi Bakre. Betrayed by blood, sold into slavery, and stripped of name and crown, he lands in the pitiless underworld of a Jamaican sugar plantation. Yet from that abyss rises not a victim — but a vessel of revolt. His journey from shackled prince to Maroon leader is not one of simple redemption, but of reckoning: with ancestry, with power, and with love.

Adunni (Atlanta Bridget Johnson), the mixed-heritage house slave who becomes both his anchor and his fire, offers more than romance. She is the moral compass. The echo of every Black woman silenced, beaten, but never broken. Her defiance is spiritual. Her love, radical.

The screenplay does not flinch. It offers no comfort to colonial nostalgia. The violence is real — not gratuitous, but grounded in historical truth. British overseers rule with iron cruelty. Black bodies are exploited, commodified, erased. But the soul of the film is not pain — it is resistance.

And that resistance comes in the form of the Maroon Priestess (played with divine gravitas by Faithia Williams Balogun). In her, we see the strength that rises when there is nothing left to lose but one’s chains. Her visions are not fantasy — they are ancestral memory breaking through the veil of oppression. When Atanda steps into the Maroon world, he steps into his own becoming.

Stylistically, Macjob weaves Yoruba cadence with English dialogue, West African majesty with Caribbean cruelty. The camera lingers on scars, sweat, salt, ritual — as if to remind us that freedom is not won in boardrooms, but in bush, in blood, and in belief.

The performances are uniformly electric. Westy Baba’s sinister overseer chills with every sneer. Kolawole Ajeyemi as Atanda’s treacherous uncle seethes with ambition. And Genevieve Edwin’s portrayal of the cunning maidservant Toro adds a layer of manipulation that tightens the noose around Adunni and Atanda’s doomed peace.

What Ireke does — perhaps more powerfully than any recent historical drama — is reframe the narrative. We’ve seen enough films about slavery as submission. This is about slavery as a prelude to rebellion. The Maroons are not background figures — they are the soul of the story. They don’t beg. They barter with destiny.

The final scenes feel like prophecy. We don’t just see freedom gained — we feel the cost it demands.

“Ireke” isn’t about the past. It’s about the past we carry forward — and the freedom we must still fight to name.