SPORTING HISTORY

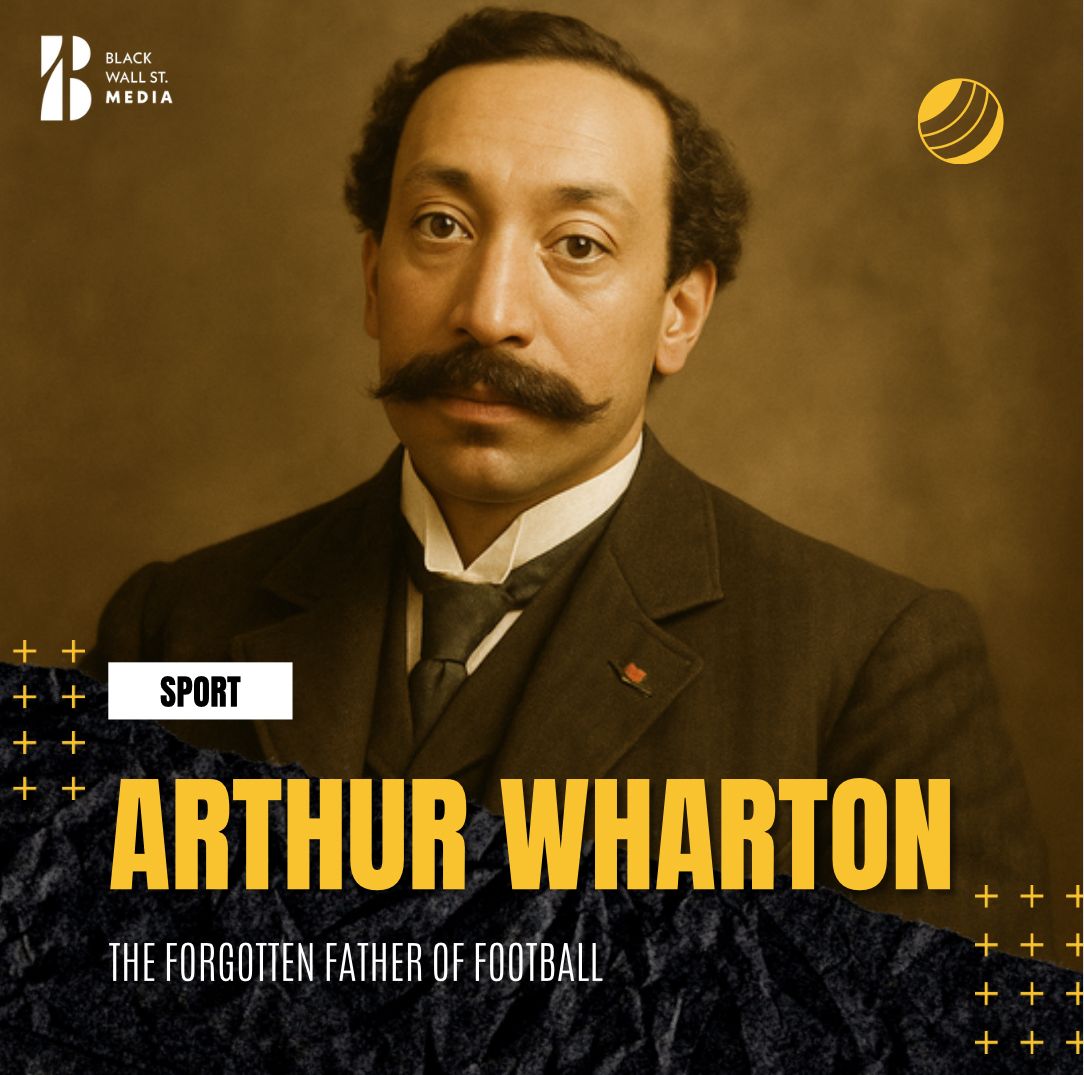

Arthur Wharton

“Honouring the Legacy of the World's First Black Professional Footballer”

BWSMCONTRIBUTOR

In the pantheon of sporting pioneers, few names carry the silent thunder of Arthur Wharton.

Though often buried beneath the weight of time and prejudice, his legacy continues to rise—undaunted and necessary. Born on 28 October 1865 in Jamestown, Gold Coast (now Accra, Ghana), Arthur Wharton was a man far ahead of his time, a trailblazer who carved a path not only through the world of football, but across the wider field of sport and civil courage.

Wharton’s roots were noble and complex: his father, Henry Wharton, was a Grenadian missionary of Scottish and West African descent; his mother, Annie Florence Egyriba, a royal of the Fante nation.

At the age of 19, Arthur travelled to England, originally to train as a Methodist minister. But as he encountered the cold winds of British soil, he found his calling not in the pulpit, but in motion—in speed, strength, and spirit. His brilliance was first recognised on the track.

In 1886, he shattered barriers by becoming Britain’s fastest man, winning the national 100-yard title in 10 seconds flat—a time so astounding it would stand unbroken for more than three decades. That alone should have secured his place in history.

But Arthur Wharton was not content with a single lane. He stepped onto the football pitch as a goalkeeper for Darlington FC and soon joined Preston North End, contributing to their famous FA Cup run in the 1886–87 season.

But it was in 1889, with Rotherham Town, that he etched his name into the record books as the world’s first Black professional footballer. His courage didn’t end there.

He went on to play for Sheffield United, becoming the first Black player in the Football League. More than a footballer, Wharton was a multi-sport marvel—also competing as a professional cricketer, cyclist, and rugby player.

He represented a vision of athletic excellence that defied the racist assumptions of Victorian Britain and forced the nation to grapple with its colonial contradictions. But Wharton’s post-sporting life reflected the cruelty of a system that had yet to honour his worth.

He laboured in coal mines, his story fading into the background of a society unready to celebrate him. When he passed away in 1930, he was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in Edlington—a final indignity for a man who had changed history.

Thankfully, memory has muscle. In 1997, following sustained campaigns by anti-racism advocates, a headstone was finally placed at his grave.

His achievements have since been rightly commemorated with blue plaques, a statue at the National Football Centre at St. George’s Park, and his induction into the English Football Hall of Fame in 2003.

To honour Arthur Wharton is to honour not only a sportsman, but a symbol of defiance and dignity. His was a quiet revolution—carried out not with banners and slogans, but with boots and brilliance.

He proved, long before the world was ready, that excellence knows no colour, and that courage often looks like a man catching balls in the mud while the crowd doubts his right to stand on the pitch at all.

As we continue to fight racism in sport and beyond, we do so on ground that Wharton helped level with every sprint, every save, and every stand he took—often alone. Let us say his name. Let us teach his story.

Let us honour Arthur Wharton not as a footnote, but as a forefather. Because without him, the game would never have been the same.