BLACK HISTORY MONTH

Reclaiming the Narrative

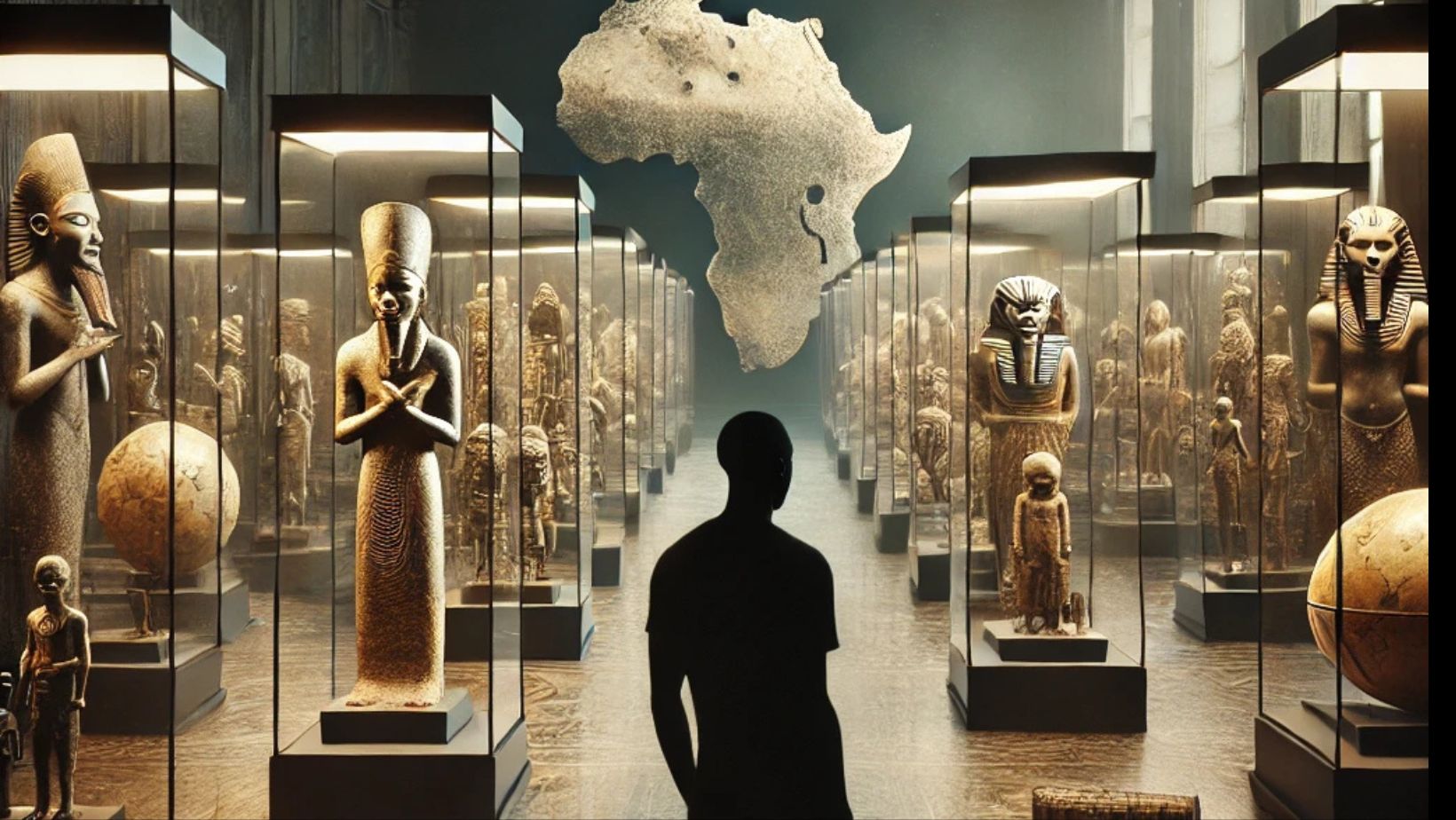

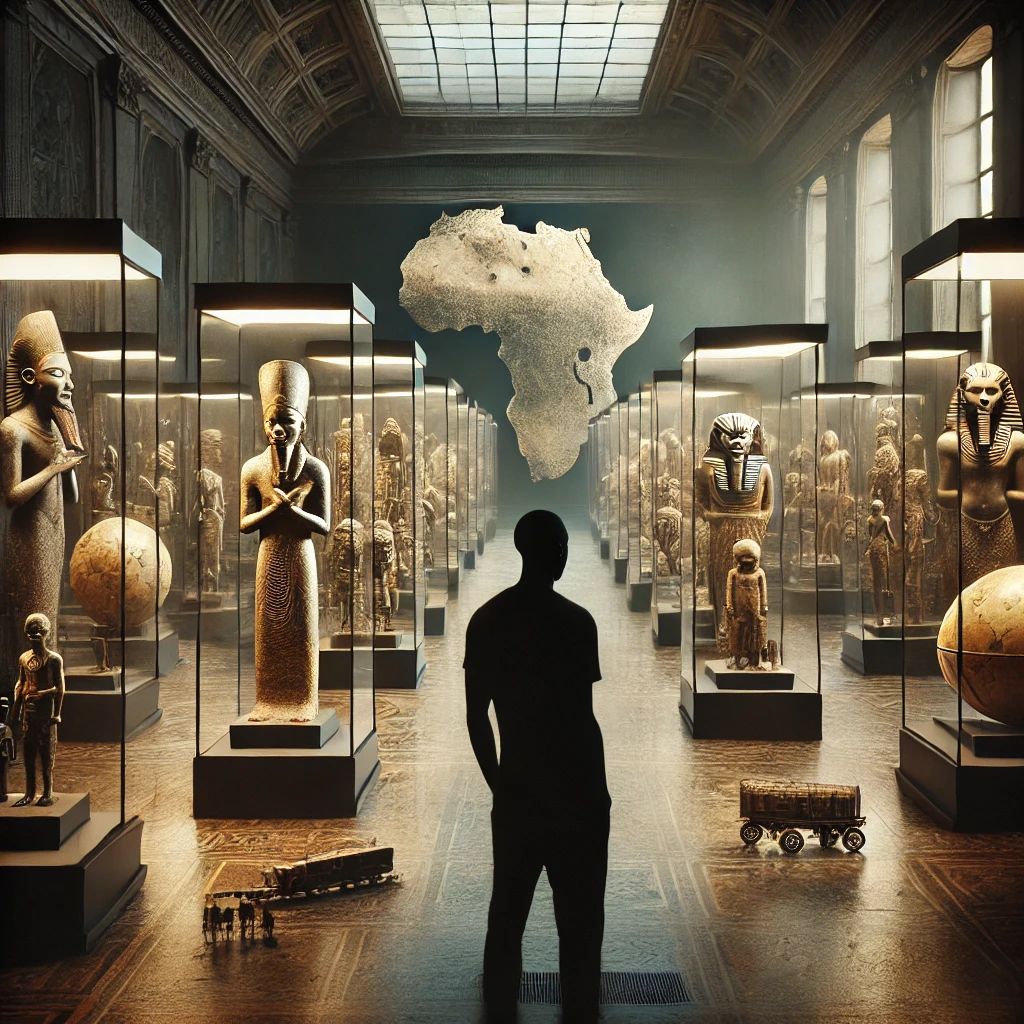

Why are Africa’s stolen artefacts still in Western museums?

“Why are Africa’s stolen artefacts still in Western museums? In the second part of her Black History Month special, Daniella Maison explores the ongoing fight for cultural restitution and reclaiming African heritage.”

DANIELLA MAISONEditor of Social Cause Issues

We all remember the opening scenes of Marvel Blockbuster Black Panther. Observing an axe in the African collection at a British museum, supervillain Erik Killmonger reminds the patronising curator that the axe was taken by British soldiers.

When the woman replies that the items are not for sale, Killmonger says: “How do you think your ancestors got these? Do you think they paid a fair price? Or did they take it, like they took everything else?”

If you walk into any European museum, you will see a wealth of curated colonial plunder. They sit quietly in glass cases beneath tasteful lighting. Display cards will afford a name, date and vague place of origin. They do not afford proper context or documentation of their spiritual, ancestral or cultural significance, They will almost certainly omit that every single one of them are all stolen.

Many museums tend to prioritise Eurocentric perspectives that promote stereotypes and biases — biases that teach inaccurate representation of non-Western culture and history to the public. Indigenous voices are often excluded, which leaves many sacred objects and artefacts to be displayed without proper context or understanding of their cultural significance.

This year’s Black History Month theme, reclaiming the narrative, speaks to amplifying the voices of the diaspora. Voices that have been silenced or stolen. Reclaiming our heritage is crucial to reclaiming our narrative.

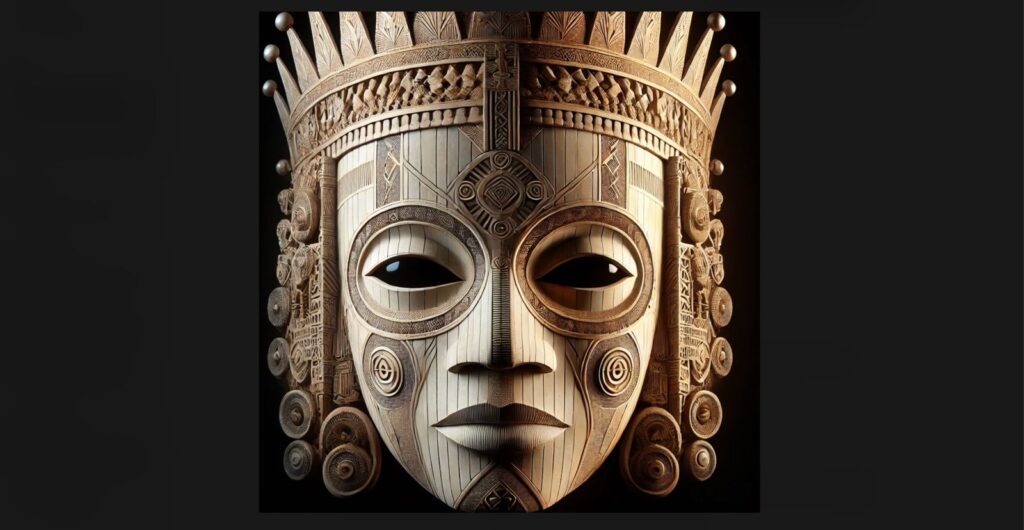

The Benin bronzes have become emblematic of the painstakingly ongoing debate over colonial loot in European museums.

Stolen by British forces from the Kingdom of Benin (modern-day Nigeria) the Benin Bronzes are a collection of over 3,000 mostly brass plaques made between the 13th and 18th centuries.

After their theft in 1897, over half of them became the property of the British Museum, and the rest were bought by museums in Germany, Austria, and the United States. Some even ended up in private collections; with Spanish painter Pablo Picasso the proud owner of one.

What is conveniently omitted from tours around these museums is that the barbaric manner of the taking of the bronzes amounted to a war crime.

Nigeria has repeatedly requested that the specimens (which are mostly housed in the British Museum) are returned. Recently, Nigeria welcomed back to Benin City just two statues out of more than 3,000.

A more sinister component of colonial loot has always been the possession of black bodies.

Sarah Baartman was brought to Europe under false pretences by a British doctor, she was as stage-named the “Hottentot Venus”, and paraded around “freak shows” in London and Paris, with crowds invited to look at her buttocks.

Today, she is seen by many as the epitome of colonial exploitation and racism, of the ridicule and commodification of black people. Not least because when she died in 1815, her exhibition continued. Her brain, skeleton and sexual organs remained on display in a Paris museum until 1974. Her remains weren’t repatriated and buried until 2002.

“We must begin to confront the reality of a past in which academic curiosity and opportunity overwhelmed humanity.” Lawrence S. Bacow.

This dehumanising history of collecting African American bodies as scientific specimens is a troubling one the world over. The Smithsonian Institution, Cleveland Museum of Natural History, and Howard University hold the remains of some 2,000 African Americans among them.

It’s high time the wants of science and the avidity of colonial mindsets ceased to exceed human rights.

The retrocession of African artefacts to African counties is vital to African identities because their full meaning can only be understood in the context of their ritual performance and purpose. Within the context of the places they were carved and created, for the people, lineages, communities and legacies they were created for.

An example of this is the Bangwa Queen, a wooden carving from Cameroon, which represents the power and health of the Bangwa people. It is one of the world’s most famous pieces of African art and has huge sacred significance for Cameroonians.

The Bangwa Queen was likely marauded by the German colonial agent Gustav Conrau in around 1899. The Dapper Foundation in Paris, France now owns the Bangwa Queen sculpture. The leaders of the Bangwa have been corresponding with the foundation, requesting its return to Cameroon. They are yet to recieve a satisfactory response.

Benin Bronzes, black bodies and a Bwanga Queen are just the top of the iceberg. The British Museum boasts that it holds more than 100,000 stolen Egyptian artefacts, it is the largest collection outside of Egypt.

After the battle of Magdala in 1868, the conquering British stole thousands of priceless items that were of vital importance to the Ethiopian Empire from the city of Magdala and the Ethiopian Christian Church of Medhane Alem.

It was stolen in such vast quantities, that it took 15 elephants and hundreds of mules to transport the loot to a nearby town for auction. Among them were up hundreds of manuscripts, a royal wedding gown, and the priceless gold Crown of Abud.

Europe’s arguments against restitution have ignored the legitimate claims of African scholars and governments for 50 years. In this never ending debate, some have the insolence to claim that western Museums are safer places for ancient artefacts than ‘unstable’ African countries. Others claim the artefacts require air conditioning to adequately preserve them.

The ancient Egyptians managed to preserve Queen Hatshepsut‘s mummy so skilfully that it remains in remarkable condition some 4,500-years later. Not to mention the schools in Burkini Faso that have developed methods to keep cool in 40 degrees help. Needless to say, Africa is capable of protecting its own belongings.

Another is that western Museums make art accessible to a large number of people. To whom? Certainly not to those from who they were stolen. Let’s face it, these are barely even arguments. Can you for one moment imagine if warmongers had stolen the Crown Jewels, or the Duchy of Lancaster (both of which are protected by armed guards) and simply refused to return them, year in and year out?

“The British Museum acknowledges the difficult histories of some of its collections, including the contested means by which some collections have been acquired such as through military action and subsequent looting … In the case of the Benin bronzes, the museum visited Benin City in 2018 to talk about plans for a new Royal Museum in Benin City and how the museum could help.”

In effect, they have offered to loan the people of Benin their own artefacts. The self-partiality of this statement from the British Museum is quite staggering. This is not the kind of talk that will end the cycle of colonialism and imperialism, it perpetuates it.

The British Museum is guilty of exhibiting “pilfered cultural property”, by a leading human rights lawyer who is calling for European and US institutions to return the wealth of treasures that were stolen.

Geoffrey Robertson QC said: “The trustees of the British Museum have become the world’s largest receivers of stolen property, and the great majority of their loot is not even on public display.”

What we do know is that Belgium’s Royal Museum for Central Africa alone has 180,000 objects, Germany’s Ethnological Museum has 75,000, France’s Quai Branly Museum has almost 70,000, the British Museum has 73,000, and the Netherlands’ National Museum of World Cultures has 66,000.

As attitudes continue to change and countries begin to take responsibility for their colonial pasts, more and more victims of colonisation are beginning to demand the return of their belongings. These objects preserve and share African history, traditions, and cultural identity in a way that is tectonic to indigenous communities and, in a broader sense, the diaspora.

No less than 90% of African cultural property resides in European museums, according to a report commissioned by French President Emmanuel Macron, who has finally decided that it must be returned.

This is a time for humility. Shockingly, many still argue that the empire also brought benefits, including education, enlightenment and legislation. Worse still, YouGov found 44% of Brits are proud of Britain’s history of colonialism.

The hundreds of millions that were mistreated, raped, tortured, pillaged and murdered remain shrouded in propaganda, secrets and lies. These countless many imperial wrongs cannot be remedied, but colonial countries can no longer, without shame, profit from them.

The Horniman Museum in south-east London in recognising this, has already returned 72 items, including some Benin Bronzes, to African ownership – making it the first in the UK to officially take such action on this scale.

In 2024, the University of Cambridge returned 39 artefacts to the government of Uganda (I must add that this is technically a three-year loan). We must keep having this conversation until the rest follow suit.

It’s not just an ownership debate. As a global community, it is highly offensive to see stolenlegacies exhibited as trophies. This is not an art debate. Much of the spoils in European museums have become known internationally as art over the many decades they have been displayed by Western museums, but they have a deep spiritual significance which precedes this.

African artefacts have spiritual significance and are considered living beings by their societies of origin. They are alive with meaning and legacy. They speak to their descendants across centuries and bestow identity, pride, legacy and enrichment. When the colonial Brits misappropriated them, it led to the loss of African cultural heritage.

The governor of Easter Island, tearfully expressed the pain of too many when he spoke of Hoa Hakananai’a remaining in the UK: “You, the British people, have our soul”.

We are not yet near to a full imperial reckoning, but we can push for the the arc of history to be bent in the right direction.

“What became of the Black People of Sumer?” the traveller asked the old man, “for ancient records show that the people of Sumer were Black. What happened to them?” “Ah,” the old man sighed. “They lost their history, so they died.”

-A Sumer Legend.

SECURE YOUR TICKETS NOW for the 2nd Spirit of the Caribbean Annual Ball & Black Honour Awards on Saturday, October 26, 2024, from 7.30 pm to 02.00 am.

The night features a reception, networking, and awards ceremony honouring those who have made significant impact within and beyond our community. Post-awards, prepare for live entertainment and dancing until 02:00 am. The event, a symbol of shared heritage, showcasing Caribbean Excellent.

Dress code is black tie.

Tickets can be purchased on Eventbrite (booking fees apply)

or from Event Connoisseurs: with no booking fee.

For more details, contact us at

enquiries@eventconnoisseurs.com