BY AMANDA J. CALHOUN

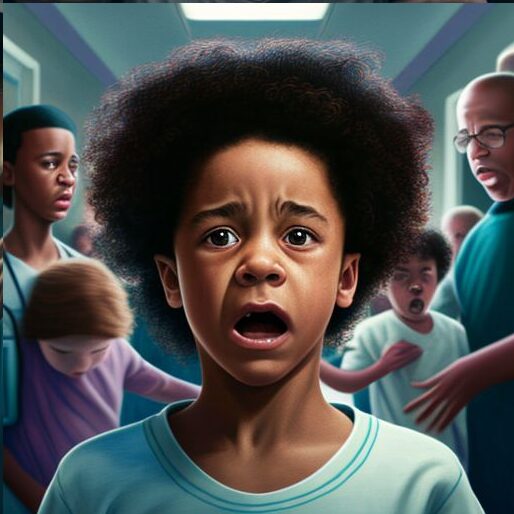

“Can you just restrain him already?” screamed the nurse supervisor.

“Why won’t that kid shut the fuck up?” a male mental health worker yelled.

“I can handle it. Thanks for your help, guys,” I replied. Both workers—both white—stomped off.

On the outside, I kept my voice level and calm, because as a Black woman, I don’t have the freedom to yell or curse at work without repercussions. But on the inside, I was irate about their lack of empathy and compassion toward a child entrusted in our care. I was the on-call psychiatrist and had just arrived on the child inpatient unit after being paged for a behavioral code. A 10-year-old male patient whose autism spectrum disorder was yet to be diagnosed was threatening to hurt himself and throwing cups of water at staff. When he saw me, he ran up to me, tears streaming down his face.

He could have been my cousin—with a caramel skin tone like mine and dark-brown, thick curly locks. I’d developed a good therapeutic relationship with him, probably because I treated him like a human who was struggling. But I had also taken the time to observe him. I knew that loud noises triggered him and that he had trouble with transitions. When staff changed shifts, noisily arriving and departing, he tended to become upset. And that was exactly what happened that day. A West Indian nurse and a Latina nurse remained at my side, expertly de-escalating the patient using psychiatric techniques that were tailored to his needs.

He did not, in fact, end up needing restraints.

Many of my colleagues had branded him as “manipulative and violent,” common racist tropes I have heard colleagues use to describe Black and Brown patients. I watched the same psychiatric colleagues treat white children who proudly use the N-word with patience and understanding. “No—they’re struggling, you know,” white staff often tell me when I inquire whether they have told these patients that hate speech is unacceptable.

We are in the midst of an adolescent mental health crisis. But Black youth have been in crisis for decades.

Black youth suicide rates are rising faster than any other racial/ethnic group in America. Black youth ages 13 and younger are twice as likely to die by suicide compared to their white peers. Yet Black youth are less likely to access and remain in mental health care. Attention is often focused on cultural stigma in the Black community or lack of economic resources. What is rarely talked about is the racism that Black youth experience within the health care system.

A recent Yale study found that Black children are nearly twice as likely to be physically restrained in the emergency department compared to white children. Black children, like my patient, are diagnosed with—and thus treated for—autism spectrum disorder on average at almost 5 and a half years old, about six months after white children, even though their parents may have first expressed concerns about their development years earlier.

Studies will often explain this disparity by citing lack of access to care, the wealth gap, and low socioeconomic status in Black populations—while usually failing to acknowledge that these issues are caused by the intentional, racist economic oppression of Black Americans due to white supremacy.

But a large contributing factor to these racial disparities is the frank neglect and subpar treatment of Black children by predominantly white mental health providers. If we want to improve Black youth mental health, we desperately need more Black mental health care professionals. And we need them in positions of power and influence.

Psychiatry is a white-dominated field, and I am constantly reminded that as a Black woman, I will never fully belong. When I bring up white staff’s differential treatment or point out the unprofessional and harsh descriptors they use when talking about Black patients (and document in patient charts), they are protected by administrators, and I am routinely targeted and retaliated against by white staff. Retaliation is often sneaky, cowardly—“telling on me” to their nursing supervisors for going against treatment plans they never communicated, talking to me in their offices about “being less intense” when I stand up for patients, interrupting me and ignoring my questions (and even, on occasion, yelling in my face).

I am forced to find strategic ways to advocate for my Black patients, while constantly watching my back—and I should not have to. Often, Black nurses and mental health workers come to me in secret to discuss unfair treatment they have received while attempting to stand up for Black patients. They come to me for help because if they report the behavior, they risk being further targeted.

Many Black mental health providers are forced to endure added stress and burden that white colleagues do not face: the burden of speaking up in a system that was not made to protect us.

To be sure, there are white mental health professionals who are committed to racial equity—but unfortunately, in my experience, they are the exception, not the rule. We desperately need change.

To start, it’s useful to clarify the different mental health roles in a hospital. There’s the psychiatrist, who is responsible for managing medications and directing treatment—but in reality, psychiatrists spend the least amount of time with patients.

There are nurses, who carry out the psychiatrists’ orders and provide critical frontline knowledge of when physical restraints or extra medications are needed on the hospital unit.

There are mental health technicians, who keep the patients safe on the inpatient psychiatric unit by neutralizing conflict, helping children take their medications, and engaging in therapeutic activities with the patients.

Psychologists play an important role in managing therapy groups, and social workers, in addition to therapy, are also crucial to ensure that patients have a safe discharge plan.

The truth is that to bring more Black individuals to all of these roles, we have to start with money. We need to go to colleges—even elementary and high schools—to recruit Black students who are interested in the mental health field, and to impress upon them how much Black psychiatrists and other mental health professionals are needed.

Black students are the most likely to have higher student debt, so it’s crucial to fully fund training and certification, whether that’s to become a psychiatric nurse or a mental health tech.

When it comes to psychiatrists, only 2 percent are Black. So we also need to invest in programs that are committed to increasing the Black medical student pipeline, like the White Coats Black Doctors Foundation or medical schools associated with historically Black universities, including Xavier University’s new medical school.

Few Black psychiatry workforce pipeline programs exist, and they often do not fully cover medical school tuition.

One such program, funded by the American Psychiatric Association, provides mentorship, funding to attend an APA conference, and financial resources for Medical College Admission Test preparation. But we need many more programs like this one if we want more Black psychiatrists.

And we need to emphasize retention, not just recruitment.

Black mental health professionals, like me, are not only witnessing the racism that our Black patients experience; we are also targeted by anti-Black racism in the workplace ourselves, from both our colleagues and patients. My Black colleagues are commonly called the N-word by white patients and often receive no support from their white coworkers.

The first time I was called the N-word, it was by an older adolescent patient who was stable and close to discharge. Even though it happened in front of a crowd of white staff and supervisors, not one of them asked me if I was OK.

The only person who supported me—first checking in with me and later going back to the patient and telling him to apologize—was a Black nurse.

There needs to be accountability for racist behavior in the workplace so that Black mental health professionals can feel safe and protected when advocating for our patients and ourselves. We need the power to shape workplace practices and provide crucial perspectives and expertise.

If Black mental health professionals are hired but not placed into positions of power and influence, then there will be minimal change and poor retention in the spaces that need them most.

Some hospitals have racism reporting systems, but it is still extremely difficult to report a white colleague for racist behavior toward patients and staff. White workers are often protected by white people in power, such as nursing supervisors or medical directors.

Further, the individuals who are in charge of interpreting and responding to reports of racism in the workplace are often not experts in mitigating racism, so the reporting system is minimally effective.

Our mental health workforce should reflect the population it serves, and right now, Black individuals are extremely underrepresented.

If we truly want to improve the mental health of Black adults as well as children, we need to get busy.