Honoring the Brilliance of America’s Black Wall Street

Another overlooked chapter in our history lessons: Black Wall Street.

Why did our textbooks omit the tales of African Americans who established their banks, collaborated with magnates like the Rockefellers, and thrived as entrepreneurs, all well before the Civil Rights Movement’s inception?

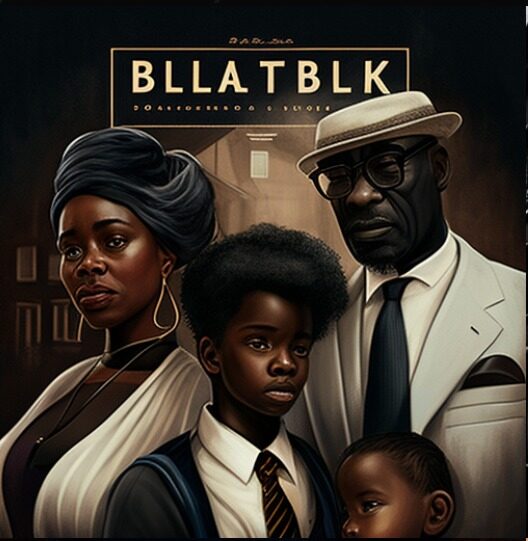

Yes indeed, long before desegregation, America had a black middle class that was thriving alongside pockets of the white elite.

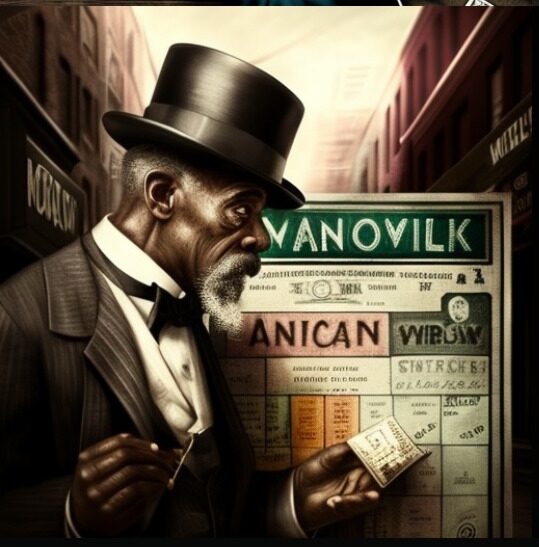

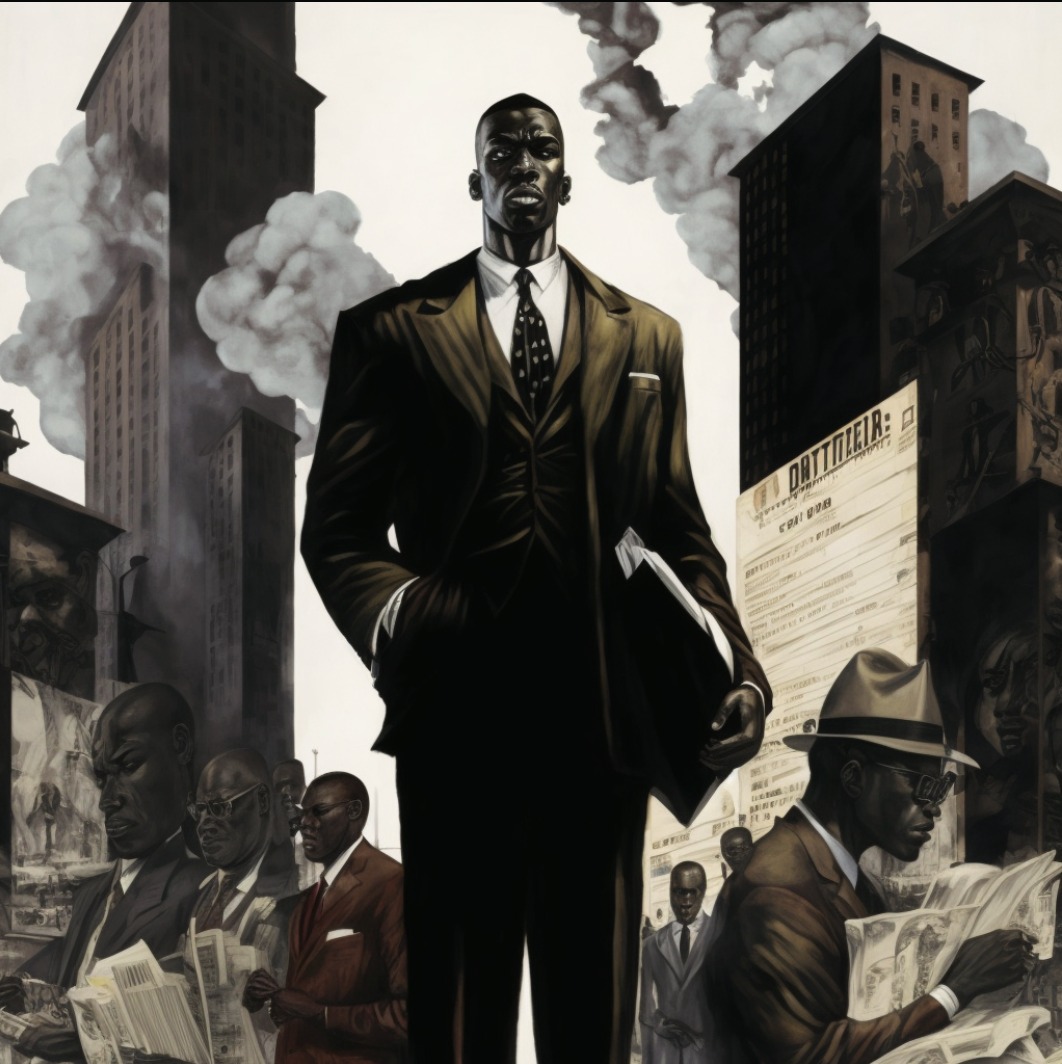

With diligent searching, you’ll uncover historic images of African Americans donning sophisticated tuxedos and top hats, cruising in luxury vehicles, and overseeing bustling financial hubs.

These visuals appear out of place, portraying a facet of black history that stands in stark contrast to the prevalent narratives of Jim Crow atrocities and the arduous journey of civil rights.

Yet, for a fleeting moment in time, Black Wall Street hinted at a future filled with intriguing possibilities…

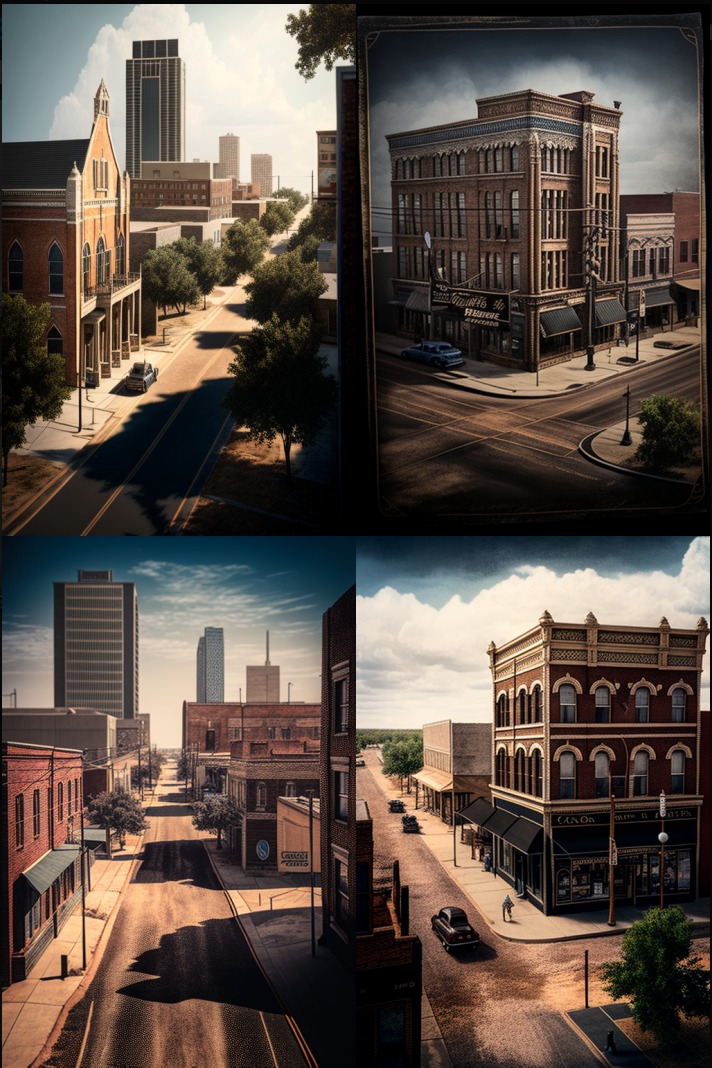

Durham, NC, Richmond, VA and Tulsa, OK; these are the three American cities at the centre of this story.

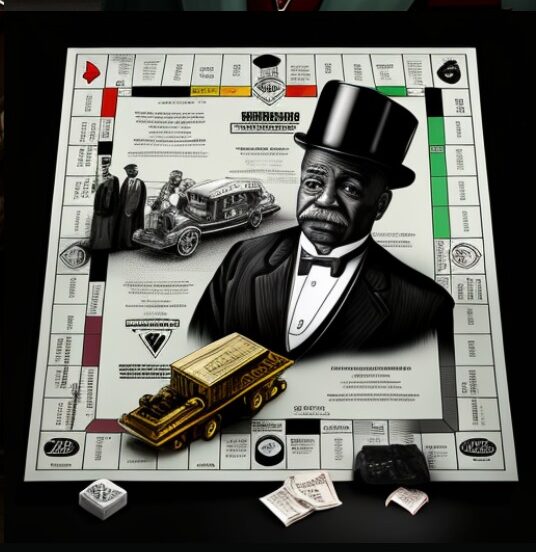

Together, they blossomed into what became known nationally as “Black Wall Street,” a turn of the century trifecta of African American economic success, from the smallest of mom-and-pop-shop owners to bankers and oil barons.

Commerce that was owned by, run for, and benefitting of black communities were precious but growing anomalies in post-Civil War, Jim Crow America.

And Black Wall Street was at the epicentre of it all…

The very first African American Bank was founded in Durham, NC, also home to North Carolina Mutual insurance, which to this day, remains the largest and oldest African American life insurance company.

Durham’s Perrish Street was like the Champs Elysées of black business owners, truly becoming the world’s epicentre for black finance.

Durham in North Carolina, Richmond in Virginia, and Tulsa in Oklahoma are the trio of cities pivotal to our narrative.

United, they flourished to form what is now famously called “Black Wall Street,” epitomizing early 20th-century African American prosperity. This ranged from modest family-owned ventures to the realms of banking magnates and oil tycoons.

Businesses that were owned, operated, and primarily serving the black communities were rare gems, yet steadily emerging in the backdrop of post-Civil War, Jim Crow-era America.

Over in Richmond, Virginia, whose Jackson Ward neighbourhood had a booming business and entertainment scene, the first ever bank to be chartered by a black woman in America, opened in 1903 by Maggie Walker. St. Luke Penny Savings Bank survives to this day, the oldest continuously operated African-American-owned bank in the United States.

Durham, NC, Richmond, VA and Tulsa, OK; these are the three American cities at the centre of this story.

Together, they blossomed into what became known nationally as “Black Wall Street,” a turn of the century trifecta of African American economic success, from the smallest of mom-and-pop-shop owners to bankers and oil barons.

Commerce that was owned by, run for, and benefitting of black communities were precious but growing anomalies in post-Civil War, Jim Crow America.

And Black Wall Street was at the epicentre of it all…

In Richmond, Virginia, the Jackson Ward district was alive with thriving businesses and a vibrant entertainment landscape. It was here in 1903 that Maggie Walker established the first bank ever to be chartered by a black woman in America. The St. Luke Penny Savings Bank still stands, holding the distinction of being the longest-running bank owned by African-Americans in the U.S.

Durham in North Carolina, Richmond in Virginia, and Tulsa in Oklahoma are the trio of cities pivotal to our tale.

United, they emerged as the acclaimed “Black Wall Street,” symbolizing early 20th-century African American prosperity that ranged from modest family-owned businesses to banking moguls and oil tycoons.

In the backdrop of post-Civil War, Jim Crow-era America, businesses owned by, managed for, and serving the interests of the black community were rare yet burgeoning gems.

At the heart of this evolution stood Black Wall Street…

Walker’s bank stood out for its genuine compassion and commitment. As she eloquently stated, “Let us put our money out at usury among ourselves, and reap the benefit ourselves. Let us have a bank that will take the nickels and turn them into dollars.”

Ultimately, the bank was sold for a staggering $4,986,344.40, positioning its owner among the most successful black entrepreneurs globally.

During an era when black home ownership was a rarity, his residence was particularly noteworthy, even more so when contrasted with an image of his humble beginnings.

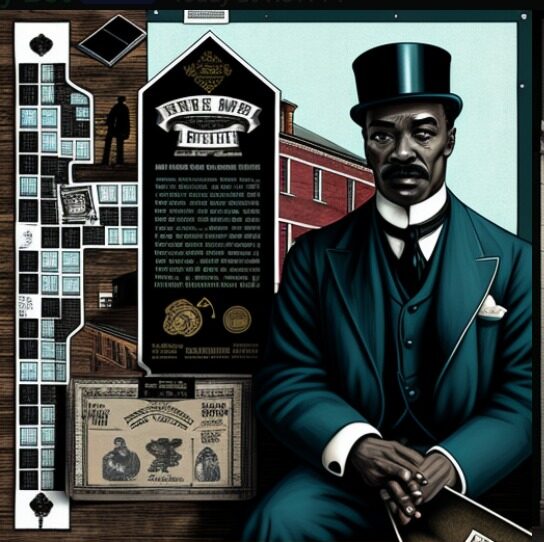

Venturing deeper into the South, much of Durham’s business acumen can be attributed to two trailblazing African American entrepreneurs: John Merrick and Charles Spaulding.

Born into the chains of slavery, Merrick’s journey from bondage to business mogul is a testament to his determination, resilience, and sheer courage.

He acquired literacy skills at a Reconstructionist school, flourished in the barbering trade, and eventually ventured into the insurance sector with North Carolina Mutual.

Merrick and Spaulding were frequently celebrated as shining examples of Booker T. Washington’s vision of “black industry leaders.”

The prosperity of Durham leaned heavily on prominent African American figures like Booker T. Washington, who bridged connections with the white elite.

Given the limited government support for Black schools, substantial investments in black businesses, especially from white benefactors, stood out as rare occurrences in the southern landscape of that era.

It’s worth noting that the prosperity wasn’t evenly shared, especially in Durham’s less affluent Hayti community. The role of certain white benefactors can’t be overlooked, and paradoxically, neither can segregation.

Prior to integration, in cities like Durham, African Americans primarily banked with black-owned institutions, which facilitated loans and bolstered black enterprises.

However, as the Civil Rights Movement surged, desegregation mandated white banks to be more inclusive. This shift led to capital, which had traditionally supported black banks, diverting towards mainstream Wall Street.

As a consequence, financial resources became more distant from the communities they once served. With integration’s dawn in the US, the outflow of black wealth accelerated.

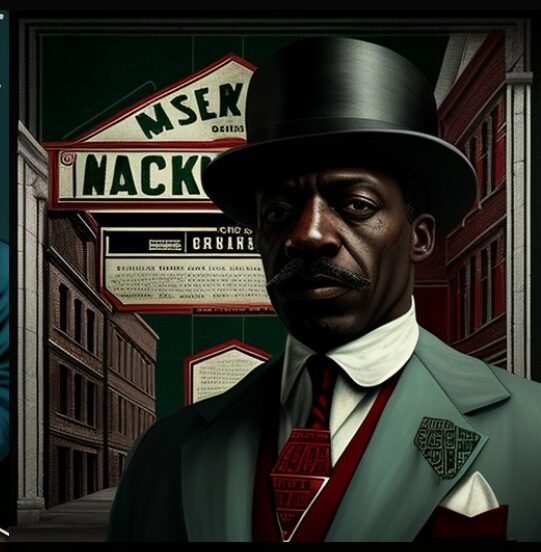

Our journey culminates in Tulsa, evoking a mix of sentiments. In the 1910s, the oil-rich region of northeast Oklahoma, particularly the Greenwood district in Tulsa, was a beacon of prosperity.

This neighborhood pulsated with life: vibrant dance halls, an influx of black-owned stores, and a distinctive prevalence of black homeownership.

The segregation policies compelled the black community to cultivate and procure what they couldn’t access in the white-dominated areas. Greenwood turned this adversity into an advantage, fostering a self-reliant economy that amplified the growth of local enterprises.

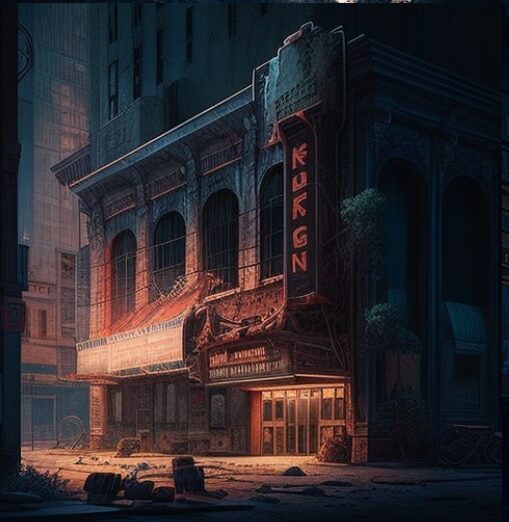

Let’s glimpse a moment from that era: Here’s John Wesley Williams with his spouse, Loula Cotten Williams. As the Tulsa Historical Society notes, “John served as an engineer at Thompson Ice Cream Company, and Loula was an educator in Fisher. Together, they owned the Dreamland Theatre.”

By 1921, Greenwood had earned the moniker “the Negro Wall Street”, now fondly remembered as “the Black Wall Street”.

The establishments lining Greenwood Avenue included the practices of most of Tulsa’s black professionals – from lawyers and doctors to journalists.

Reports indicate the existence of about 600 black-owned enterprises, a multitude of grocery stores, cinemas, private airplanes, a bank, hospital, and an educational institution.

However, the thriving district faced a cataclysmic event in the Spring of 1921: the Tulsa Race Riot.

The flashpoint was the detainment of a young black individual, suspected of assaulting Sarah Page, a white elevator operator.

Most current evidence suggests the possibility of a mere accident, with Rowland perhaps accidentally stumbling upon Page.

Yet, this incident unleashed a devastating turmoil in Tulsa.

The Tulsa event, more aptly termed a massacre than a riot (since “riot” suggests a balanced confrontation) is a harrowing testament to unchecked racial animus. Initially, the white-owned Tulsa Tribune ignited the flames. Soon after its coverage, masses gathered outside the courthouse where Rowland was detained. Approximately 75 black individuals, many of whom were WWI veterans, arrived to defend Rowland, only to face an enraged white mob numbering in the thousands.

By the night’s end, the Oklahoma National Guard was deployed, resulting in every business razed, leaving 9,000 residents without shelter during winter. It stands as America’s most devastating riot, marking the annihilation of a vibrant community through racially charged violence.

Yet, amidst the chaos, stories of unity emerged. Families like the Zarrows offered sanctuary to black residents in their homes and shops. The Red Cross played a pivotal role in delivering aid. The aftermath, however, was brutal. The financial impact on the black community equates to billions in today’s currency. While the city resurrected, the haunting past was often silenced.

Though Greenwood found its feet again, the glory of Black Wall Street dimmed over time. Reverend Solomon Sir Jones’ rare footage serves as a testament to the resilience of the Black community post the Tulsa tragedy.

Ironically, desegregation marked the beginning of Black Wall Street’s downturn. As African Americans began shopping in other neighborhoods, their economic stronghold waned. Later, in the 60s, government-led urban renewal efforts further diminished its influence, causing arguably more lasting harm than the massacre itself.

This chapter of history remains underrepresented in mainstream discourse. Unearthing these narratives is pivotal to grasp the rise and fall of Black Wall Street. While these conversations might be challenging, looking forward necessitates acknowledging both the triumphs and tribulations of the past.

The entrepreneurs of Black Wall Street epitomize tenacity. Emerging from the shadows of slavery and overcoming insurmountable odds, they established flourishing enterprises. Their spirit remains a beacon for every ambitious soul, proving that adversity can be overcome. So, to every entrepreneur and visionary, let’s honor the indomitable spirit of America’s Black Wall Street.