HISTORY

Grenada's Unsung Heroes: The Island's Pivotal Role in World War II

“Throughout the tumultuous period of World War II, the Caribbean played a pivotal yet often overlooked role. Islands like Grenada showcased adaptability and resourcefulness, not only surviving but actively contributing to the global war effort.”

Black Wall St. MediaContributor

Britain’s approach to ensuring social harmony in its colonial empire involved cultivating a deep belief among the colonies that Britain was mighty, benevolent, and fair.

The colonies saw themselves as privileged to be “His Majesty’s Subjects.” A majority of the colonial populations held allegiance to the Crown, showing respect for its representatives and regulations.

This loyalty was further reinforced in places like Grenada with festivities marking the coronation of a new King and Queen, paralleled across the British Empire.

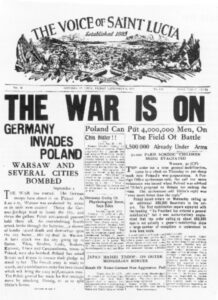

When Britain joined World War II on September 3, 1939, the people of Grenada held warm sentiments towards their colonial parent.

Grenada stood on the cusp of various transformations, sparking hope for improvements in their challenging social and economic situations.

The Royal Commission, known as the Moyne Commission after its leader, was established in 1937 to delve deep into Grenadian life.

In 1924, the previously protested Crown Colony Government was supplanted by a constitution, introducing partial public representation and granting women voting rights. Significant advancements were also made in education, health, and communication.

Yet, as Britain faced existential threats, Grenada’s modernisation aspirations had to be paused.

Despite past criticisms of Britain’s oversight of Grenada or their limited self-governance, Grenadians united with a surge of patriotism as the war commenced.

Their loyalty to Britain was further solidified by their distaste for the totalitarian ideologies spreading in Europe, which countered the democratic values they admired in Britain and aspired to for themselves.

However, Grenadian patriotism was tinged with apprehension, knowing well that their lifestyles would undergo vast changes. Given Grenada’s reliance on imports, primarily through sea transport, for essentials, there was an underlying concern.

This war differed from earlier ones; Britain was not merely striving for European power equilibrium. The invasion of Poland by Hitler stirred concerns that Britain might face a similar threat. Consequently, upon Britain’s entry into the war, its colonies, by default, were drawn into the conflict. By December 1941, Britain and its colonies found themselves at odds with not just Germany but also Finland, Hungary, Romania, and Japan.

During the wartime, Grenada was governed by Sir Henry Bradshaw Popham, K.C.M.G., M.B.E., succeeded by Sir Arthur Francis Grimble K.C.M.G., M.A. on 18th May 1942. Their responsibilities transcended routine administrative duties; they had to safeguard Grenada from external threats and potential internal espionage.

Immediate Responses Following the War Declaration

Upon hearing the War Declaration, the unofficial representatives of the Legislative Council were compelled to convey their unwavering loyalty to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, expressing:

At this pivotal time, with the Empire’s Armed Forces summoned to champion the principles of justice, the residents of Grenada, via their elected officials in the Legislative Council, wish to assert their enduring loyalty to Your Majesty’s Throne and Person.

They wholeheartedly offer their services in any capacity deemed beneficial to our shared objectives by Your Majesty’s Ministers in the UK.

Prior to the war declaration on 26th August 1939, an urgent message was sent to the Governor, including an Imperial Order-in-Council that expanded the Imperial Emergency Powers Act to cover Grenada.

Reflecting on the experiences from the previous World War, the government swiftly implemented price controls. This action aimed to prevent merchants from hiking prices, which could have caused immediate hardship for the citizens. Although living costs would inevitably increase, the escalation was tempered by these regulatory measures.

An authoritative body was promptly established to oversee trade and initiate necessary measures to both stabilise the economy and manage resources during the war.

A primary focus was to regulate imports and monitor the pricing of commodities. Notably, the government did not influence commercial banks, which subsequently lowered their interest rates to 1% for savings accounts starting 1st October 1939.

Defensive regulations specifically tailored for Grenada were rapidly formulated, along with the initiation of mail and telegraph surveillance. Sequentially, various ordinances similar to those from World War I were enacted for the colonies, with the Legislative Council of Grenada endorsing them.

Some of these, such as the Trading with the Enemy Ordinance, might have seemed tangential. However, others led to deeply sorrowful outcomes, as seen when a ship transporting Jews escaping probable death in Germany was denied entry in Jamaica.

The war brought additional financial burdens for Grenada. Establishing the Censorship Service, the Competent Authority, providing aid to government staff on military assignments, securing medical supplies and blackout materials for governmental entities all demanded funding.

To cover these extra costs and counterbalance the drop in government revenue due to import restrictions, export taxes were imposed on nutmegs, mace, and cocoa. Given that the prices of these goods had surged during the war, the tax primarily affected affluent planters and those with substantial financial means.

Contribution to the War Effort

Beyond financial contributions for war-related costs within Grenada, the Grenadian community displayed significant generosity towards the broader War Effort.

A War Purposes Committee was established, primarily focusing on fundraising and determining how to allocate the collected funds. They managed to gather a total of 20,069 18s and 3d.

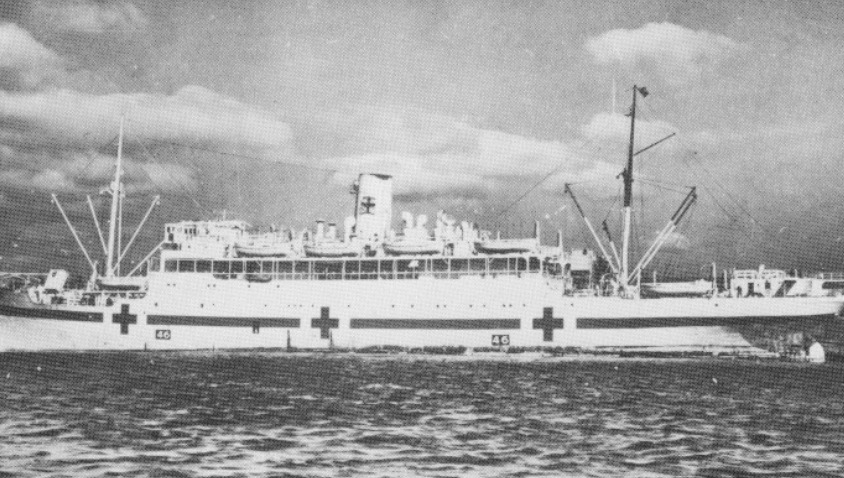

This sum was used to fund various initiatives, including the procurement of a fighter jet, contributing to half the cost of a mobile canteen, making donations to both the British and local Red Cross (specifically for creating care packages for Grenadians on the frontline), and supporting several charities that aided those affected by the War.

The West Indian War Services Fund was also a beneficiary of Grenada’s monetary support.

Echoing their efforts during World War I, middle-class women not only knitted essentials such as balaclavas, scarves, gloves, and socks for the soldiers deployed overseas, but they also passed on these skills to their domestic helpers.

Recognising these women’s invaluable contributions, many were honoured with certificates from the Red Cross post-war, celebrating their efforts in ensuring the soldiers stationed in Europe remained warm.

Additionally, a significant number of Grenadians financially supported the cause by investing in War Bonds.

Grenadians in Military Service

In 1939, foreseeing the outbreak of the war, the Grenada Volunteer Force and Reserve, which had remained active post-World War I, combined with the Police Force.

This consolidation resulted in the formation of the Grenada Defence Force, which, upon the war’s declaration, was tasked with defending crucial positions according to the island’s Defence Scheme.

Simultaneously, the Grenada Volunteer Reserve was established. Its members received military training and were provided with uniforms and firearms. In 1944, the Southern Caribbean Force came into existence, led by both British and Caribbean officials.

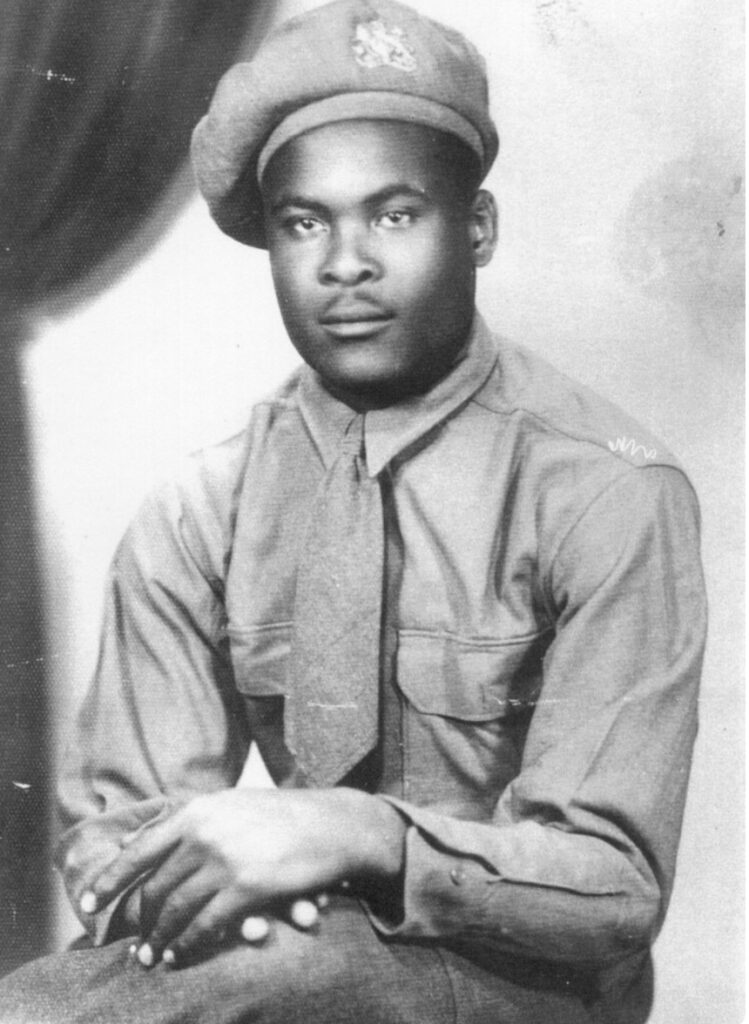

The Grenada contingent of this force, under the Windward Islands Garrison, enlisted 139 individuals.

These servicemen were not confined to Grenada but served across various Caribbean islands.

While some signed up out of patriotism, others viewed enlistment as a steady source of income and an opportunity for travel. Notable Grenadian servicemen in this group included Allan Gentle, Ben Jones, Derek Knight, and Claude Bartholomew.

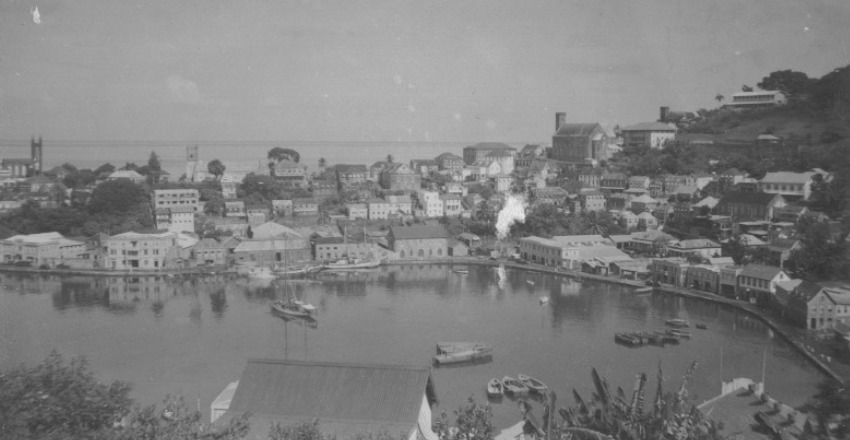

Two military divisions, the infantry and artillery, were stationed near St. George’s. The former was accommodated in barracks which later served as classrooms for the Grenada Boys’ School post-war.

Two key artillery placements were set up, one at Ross’ Point and the other at Richmond Hill. The existence of these forces offered Grenadians a sense of security, even though German forces could have theoretically taken over any of the islands if they had wished.

For the duration of the war, Grenada was under the supervision of a British Commander, Commander Castle, who also oversaw censorship duties, aided by Miss Laurie Harbin and Miss Mollie McIntyre. Later, Mr. H.H. Pilgrim also took on censorship roles.

The U.S. also had a footprint in Grenada, maintaining an American Consulate and a readiness vessel commanded by the American Consul, Charles Whitaker. U.S. military personnel often made unannounced visits to Grenada.

On one such instance, they brought heavy artillery on large trucks, only to leave without installation after exploring potential sites.Several Grenadians volunteered for the British and Canadian Armed Forces.

Notable Grenadian servicemen abroad included Julian Marryshow, who served in the Royal Air Force, and Leo de Gale and Mike Bain, who were part of the Canadian Army. Additionally, some Grenadian women joined the Auxiliary Territorial Service (A.T.S.) in Britain, including Betty Kent-Mascoll. Grenadian forces overseas generally had commendable records, despite occasional racial prejudice.

Herbert Payne, an officer of the Southern Defence Force, was frequently seen on his motorcycle at Ross’ Point, accompanied by a young aide. Given fuel rationing, bicycles and motorcycles became popular transport mediums.

Mr. Irie Francis served with distinction in the British Army, witnessing combat in regions like Egypt. After the war, he contributed significantly to Grenada’s Police Force and later established Grenada Security Services, the island’s premier private security agency.

German Operatives in Grenada

Grenada harboured German operatives who aimed to gather critical intelligence on naval movements while also disseminating anti-British and anti-War propaganda.

These agents capitalised on the existing mistrust and grievances resulting from the treatment of black soldiers during the previous war. Their efforts bore fruit as they managed to convince certain military recruits to rescind their commitments, often right before their deployment.

However, loyal Grenadian citizens strived to counter this influence. Speaking to the St. Andrew’s Detachment of the Grenada Contingent, C.H. Lucas, a renowned lawyer and politician of mixed heritage, shared:

“While a handful, thankfully a minuscule group, indulge in divisive actions; while some are misguided; and while others display blatant cowardice; over fifty of our compatriots stand here today, bearing testimony to their dedication and allegiance.

I’d remind the seditious ones that their freedom to spew pro-German falsehoods is a liberty granted under the magnanimous governance of Britain.

The malicious narrative that suggests serving merely as ‘windbreaks’ for British forces is not only misleading but deserves the scorn of those informed about modern combat scenarios… As for the faint-hearted who initially enrolled, underwent medical checks, but eventually backtracked on their commitments – I have no time for such cowardice.”

There’s a notable story about two individuals who arrived in Grenada claiming to be American wrestlers named Joe “Whiskers” Blake and Joe Gotch. While records verified that such American wrestlers once existed, they had long passed away.

After hosting several wrestling demonstrations, these supposed athletes mysteriously vanished. It’s believed that “Whiskers” Blake was later detained in Trinidad as a spy and subsequently sent to Britain.

Another individual of interest was Pedrito Da Silva, who, under the guise of an agricultural expert, mingled with locals in Grenada. However, he too vanished suddenly, leaving behind baffled acquaintances.

The Caribbean’s Role in World War II

World War II, unlike its predecessor, spanned the globe due to advancements in transportation, including swifter ships, advanced aircraft, and superior submarines.

The Caribbean and Southern North Atlantic regions, which remained relatively uninvolved during World War I, became significant naval battlegrounds in World War II. This prominence arose from the region’s production and refining of oil and bauxite, essential resources for fuelling a motorised conflict.

While Grenada wasn’t a strategic center-piece, it held value. The Point Salines Lighthouse was crucial for navigation, aiding ships entering the Caribbean.

Moreover, the radio navigational system at Pearls airport guided air traffic traversing the Caribbean towards West Africa and South America. However, Trinidad bore the brunt of the Caribbean’s wartime significance, with Antigua also playing a pivotal role.

In 1941, Britain’s Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, and the United States penned the Bases Agreement.

This accord permitted the U.S. to establish bases in Trinidad, St. Lucia, Antigua, and other Caribbean locations in exchange for 50 destroyers. Consequently, two expansive American bases were constructed in Trinidad: a naval station at Chaguaramas and an air force station at Wallerfield. Trinidad served as the primary gathering point for oil tankers journeying from the Caribbean refineries to North Africa and Europe.

Moreover, the Gulf of Paria in Trinidad was a final training ground for U.S. carriers and aircraft before their deployment to the Pacific theatre through the Panama Canal.

Aircraft designated for North Africa’s Eighth Army were routed through Trinidad.

Any aircraft or vessels originating from South America had to receive clearance in Trinidad before heading to North America or Europe.

Moreover, a comprehensive censorship department in Trinidad also acted as a facade for British and U.S. operatives monitoring Latin Americans who, under Spain and Portugal’s neutrality, might have facilitated smuggling or espionage for Germany.

German U-boat Operations in the Caribbean

Due to the Caribbean’s vital supply of oil and other resources to Britain, coupled with its strategic role in the war effort, Germany sought to undermine the advantages England drew from the region. German U-boats were deployed as a critical instrument to this end, especially after the United States entered the war.

Prior to the U.S.’ involvement, Germany had respected the Pan-American Neutrality Zone established by the Declaration of Panama in 1939.

The German naval strategy aimed at disrupting the maritime passage through the Panama Canal and severing transatlantic communication. A secondary goal was to decimate oil infrastructures and tankers.

The U-boats achieved considerable success, sinking numerous tankers and cargo ships from Aruba, Curaçao, Venezuela, and Trinidad destined for England with essential supplies like oil, gas, bauxite, and sugar. Additionally, they targeted ships bringing vital goods to the Caribbean to potentially induce famine and disillusionment with the war.

For a time, the Allies found themselves helpless against the U-boat onslaught. The most distressing period was in March 1943, where 97 allied ships were sunk within twenty days. This led Winston Churchill to express his deep concern to President Franklin Roosevelt about the dire situation.

However, a pivotal moment came in 1943 when the British destroyer, HMS Petard, intercepted a German U-boat in the Mediterranean.

As the German crew scuttled their vessel to prevent capture, two British sailors risked their lives to retrieve German encryption devices. This significant capture enabled the British to pinpoint U-boat locations, dramatically shifting the war’s momentum.

The U-boat threat led to a drastic reduction in foreign maritime traffic to the Caribbean. Though Grenada wasn’t directly assaulted, nearby attacks induced widespread concern.

Local vessels stepped in to compensate for the diminished service from larger international ships, but even these were not safe from U-boat threats.

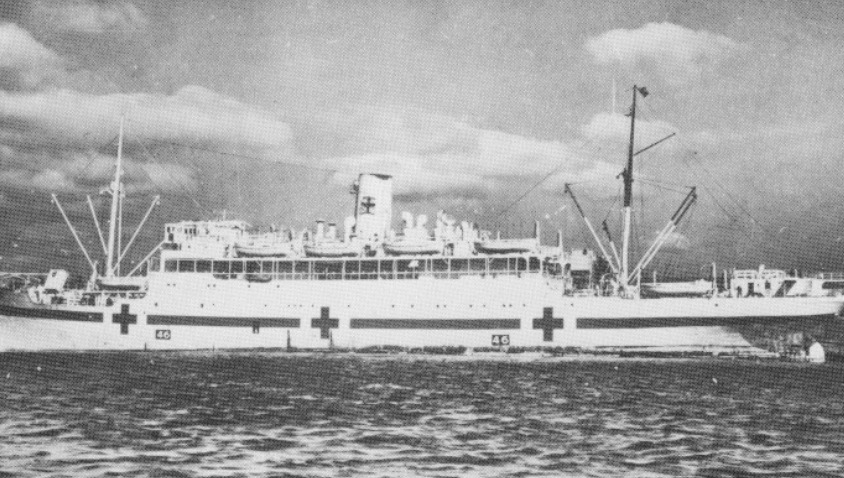

Some survivors of these encounters, including a few German sailors, found refuge in Grenada, where they were treated and then transferred to British authorities.

While Grenada was spared certain traumas, like Dominica’s experience of having deceased seamen wash ashore, there were reports of German submariners landing on smaller Caribbean islands, likely for brief respites and provisions.

It’s believed, and supported by some historians, that German submariners sometimes made brief landings on secluded Caribbean beaches, both for relaxation and to source supplies like coconuts. This showcases the often complex and multifaceted nature of wartime operations in the region.

Eileen Gentle records that:

It was also believed that U-boats used the small unprotected and often uninhabited islands of the Grenadians, between Grenada and St. Vincent for refuelling.

It is perhaps less likely that German sailors from submarines were allowed to come into St. George’s to go to the cinema, although one respondent told me that two Germans were arrested at the Roxy Cinema in Port-of-Spain.

“Blackouts” were practised regularly in St. George’s, and volunteer black-out wardens walked the dark streets, knocking at the doors of anyone who let a chink of light escape through the thick, black curtains that hung over the windows

News and Broadcasting

Introduced in the 1930s, radio was a budding technology. However, World War II significantly accelerated the growth of radio broadcasting in the British Caribbean.

The British Government recognised the medium’s potential for delivering war updates and broadcasting morale-boosting programs. Through relayed broadcasts from the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), Grenadians and their Caribbean neighbours received the same war news as the British populace.

While Grenadian newspapers supplemented these broadcasts, word of mouth became a primary mode of information dissemination, especially for news directly concerning Grenada.

For instance, while official news mainly covered the European war front, stories about nearby torpedoed ships and U-boat sightings were typically shared among men, often discreetly to avoid causing undue concern among women.

Adapting to Scarcity: Local Solutions During Wartime

At the outset of the war, a significant communication from the Secretary of State for the Colonies highlighted the expected financial strain due to the war. Governors were urged to prioritise local production, especially of food, and avoid any expenses that would use foreign exchange or create demands for non-essential goods.

The memo emphasised the importance of maintaining quality social services and avoiding any staff cutbacks. This was conveyed in a Legislative Council meeting on 29th September 1939, indicating that imports would soon be limited or entirely halted.

Predictably, Grenada soon faced shortages of everyday essentials, from petrol and wheat flour to kerosene and imported butter. The scarcity was so acute that an invitation to tea, which featured slices of bread, was an extraordinary occurrence, as recounted by Frederick McDermott Coard in his autobiography. Imported goods became rare, while biscuits made in nearby Trinidad were treasured.

This scarcity forced Grenadians to adapt and innovate. One significant change was the renewed emphasis on local agriculture. Residents turned to homegrown produce such as sweet potatoes, yams, dasheens, plantains, and breadfruits.

Local food processing methods, long-forgotten, were resurrected to make substitutes for imported goods. Breadfruit flour, made by sun-drying and pounding the fruit, became an alternative to wheat flour. Other locally processed foods like farine, cassava, and cassava cakes also regained popularity as rice and potatoes became scarce.

Innovative Grenadian cooks showcased their skills by recreating the textures and tastes of imported goods with local ingredients. For instance, pigeon peas were prepared to mimic the look and feel of canned petit pois. In the absence of butter, cream from cow’s milk was churned with salt and other ingredients to produce a homemade alternative.

The scarcity of gasoline meant that most Grenadians had to reacquaint themselves with walking or making travel plans well in advance. While essential services received some petrol, for general travel, one had to reserve a seat on the mail van weeks in advance.

These adjustments, driven by necessity, highlighted the resilience and adaptability of the Grenadian people during challenging times.

Wartime Migration to Trinidad and Economic Resilience

Despite the risks posed by submarines to local shipping during the war, these years witnessed a significant surge in Grenadian migration to Trinidad. People would queue outside shipping offices, eagerly awaiting their chance to purchase tickets. Two popular boats that frequently carried migrants between Grenada and Trinidad were The Enterprise and May I Pick.

Many Grenadians sought employment opportunities in Trinidad, attracted by jobs at American bases in Chaguaramas and Wallerfield, construction of the Churchill Roosevelt Highway, dock-work, and oilfield jobs.

These job vacancies arose as many Trinidadians shifted to new employment areas created by the war. Consequently, Trinidad introduced ordinances in 1942 and 1944, limiting immigration except for those contracted for agricultural labor.

But it wasn’t just blue-collar workers who migrated. Several educated individuals from the middle class also moved to Trinidad, opting for manual labor that offered better pay than clerical roles in Grenada.

Elton George Griffith was one such migrant, initially intending to journey on to Syria but eventually settling in Trinidad. He became instrumental in advocating for the rights of the Shouter Baptists.

Additionally, Grenadians migrated to the Dutch islands of Curaçao and Aruba, attracted by the oil refining industry. Notable migrants included Eric Matthew Gairy, a former teacher, and Rupert Bishop, the father of Maurice Bishop. From 1941 to 1944, Grenada saw a net population loss of 8,300 individuals due to migration.

Yet, amid these challenges, Grenada’s spirit remained unbroken. Despite inconveniences, the island’s economy held steady. The demand and price for Grenada’s nutmegs and cocoa, which had plummeted in 1938, surged again.

The bombing of Pearl Harbour in 1941 meant that Europe and America could no longer access nutmeg shipments from the Far East, leading to a price spike for Grenadian nutmegs. Those who had the foresight to invest in nutmeg stocks saw significant financial gains.

Local shopkeepers, although affected by import limitations, adapted by selling local produce. Their resilience was often bolstered by their dual roles as small farmers or dealers for Grenada’s exportable goods.

The Island Queen Mystery and the Carriacou Calamity

Lucy DeRiggs lost on the Island Queen, along with 66 other persons.

One of the most haunting wartime events for Grenadians was the disappearance of the auxiliary schooner, The Island Queen, on 5th August 1944. An excursion to St. Vincent had been arranged, with passengers split between The Island Queen and another vessel, the Providence Mark. The Island Queen, with its vibrant atmosphere, was the preferred choice for many of the younger passengers, some of whom exchanged their seats on the Providence Mark to travel on it.

When the Providence Mark docked in St. Vincent, there was surprise that the Island Queen hadn’t yet arrived. With time, worry set in. Despite searches, the Island Queen never reappeared. An official inquiry theorised that a fire might have consumed the ship, but many found this hard to believe. Suspicion grew that an Allied submarine might have mistakenly torpedoed the ship, especially considering no acknowledged wreckage was found. Rumours of debris like hats and clothes washing ashore fuelled this speculation.

There were other theories, including the possibility of a German submarine attack, an accidental encounter with a naval mine, or even a natural disaster involving the Kick ’em Jenny underwater volcano.

The mystery surrounding the Island Queen’s fate remains, though answers might emerge as World War II records become public.

Chiara Salhab, the owner of the Island Queen with his cousin, onboard the Island Queen.

Further tragedy struck Carriacou after the war. On 6th July 1945, what villagers believed to be a barrel washed ashore at Windward. When they attempted to open it, it exploded, taking the lives of nine individuals and injuring two more.

This “barrel” was a floating mine. This tragic event led to warnings for fishermen, with more mines discovered and subsequently destroyed safely by British naval forces.

The War Ends!

The War Ends!

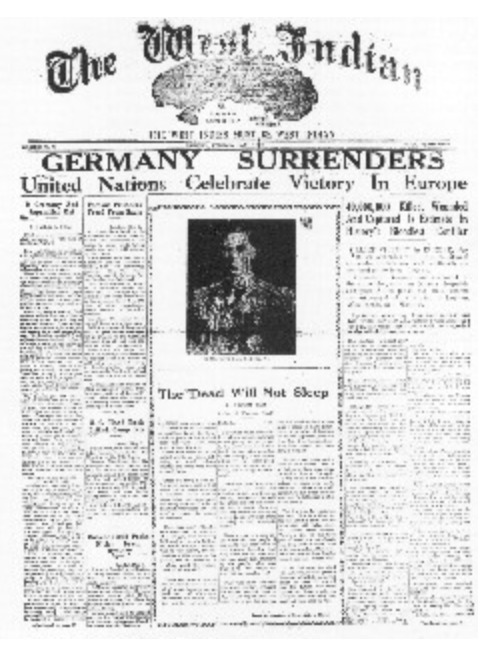

“Germany Surrenders!” the headlines proclaimed.

On 8th May 1945, Grenada, like the rest of the Allied nations, marked ‘V.E. Day’ (Victory in Europe). The island erupted in jubilation, with streets bursting with music, dance, and festive processions reminiscent of Carnival.

The euphoria continued with the celebration of “V.J. Day” on 14th August, signifying the Allies’ triumph over Japan.

In the aftermath, the government began to roll back war-time measures.

Returning soldiers were welcomed home, with many securing positions in the police force, civil service, and other sectors. Some pursued further education, while others seamlessly reintegrated into various professions.

Grenada’s Triumph in the War

Grenada’s Triumph in the War

Grenada successfully weathered the challenges of the war. Unlike the hardships endured in places like Barbados, Grenada’s residents remained nourished and resilient. Though their diets changed, they were innovative, growing and producing their own food, even if it wasn’t always their first choice.

The Grenadian spirit shone through as they adapted, maintained discipline, and showcased patience. Even amidst the chaos, they carried on with everyday life, facing wartime scares with bravery and tenacity.

Patriotism was evident, as many volunteered both locally and internationally, contributing significantly to the war cause.

The community endured the tragic loss of 56 young souls aboard the Island Queen, and others in maritime mishaps across the Caribbean and the Atlantic. With the war over, Grenada emerged more determined than ever to advocate for better living conditions, universal suffrage, and self-governance.

The war exacted a minimal toll on Grenada’s military personnel, with only three not making it back home. Flight Officer Colin P. Ross, Sgt. J.D. “Jack” Arthur, and Sgt. John Ferris, all members of the R.A.F., sacrificed their lives in European skies.

Their names found a place on the War Memorial situated in the Botanic Gardens at Tanteen. Their bravery remains a testament to Grenada’s commitment to the ideals they held dear.

Caribbean Resilience and Contribution in World War II

Throughout the tumultuous period of World War II, the Caribbean played a pivotal yet often overlooked role. Islands like Grenada showcased adaptability and resourcefulness, not only surviving but actively contributing to the global war effort.

The Caribbean region, with its strategic naval points and essential resources such as oil and bauxite, became a significant theatre for both logistics and conflict.

Places like Trinidad held immense strategic importance, serving as convoy assembly points and acting as pivotal hubs for communication and transportation.

Beyond material and strategic contributions, the Caribbean people showcased an indomitable spirit. They took up the mantle, volunteering in considerable numbers, serving both at home and abroad, and standing as a testament to the region’s dedication to a global cause.

Their sacrifices, both on the battlefront and through losses at home like the Island Queen tragedy, mirrored the global narrative of endurance and loss.

Moreover, the depth of Britain’s debt to the Caribbean cannot be overstated. The region not only provided the British Empire with vital resources and manpower but also maintained unwavering loyalty at a time when the very essence of the British colonial structure was under threat.

The sacrifices and contributions of the Caribbean people bolstered the British war effort, both tangibly and morally.

In the face of adversities, the Caribbean islands stood as pillars of support, ensuring that Britain had the backing it required on multiple fronts.

The post-war era brought about decolonisation and the eventual independence of many of these islands, but the historical bond forged during the war remains a testament to their combined resilience and camaraderie.

In conclusion, the Caribbean’s contribution to World War II transcended its geographic size.

The region provided invaluable resources, strategic locations, and most importantly, a resilient and dedicated populace that stood firmly against the tyranny threatening the world.

Their combined efforts not only ensured the survival of their own communities but played an integral part in the broader Allied victory.

The legacy of the Caribbean during this era serves as a powerful reminder of the region’s capabilities and spirit when united for a common cause, and Britain’s enduring debt to these islands and their inhabitants.

Black Wall St. MediaContributor