Health and Science

Understanding the Impact of Childhood Adversity on Brain Development

“If we're going to treat the world as colorblind, we're not going to create mental health solutions that are effective for all people.”

Black Wall St. MediaContributor

In recent years, the issue of systemic racism has been brought into sharp focus, prompting introspection and dialogue across various sectors of society.

One area where systemic racism manifests with profound implications is in the realm of childhood adversity, particularly economic strife.

A study published in the American Journal of Psychiatry reveals that such stressful experiences act as a toxic stressor that can alter brain regions tied to processing stress and trauma.

Alarmingly, this impact is significantly more severe in Black children due to their higher exposure to poverty and adversity.

This groundbreaking research, led by Nathaniel Harnett, an assistant neuroscientist at McLean Hospital and assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, utilized MRI scans to pinpoint small variations in the volume of specific brain structures.

It was observed that these changes, though minute, could accumulate as children grow and potentially influence the development of mental health disorders later in life.

This study is not isolated in its findings.

It adds to a burgeoning body of research examining how societal factors like racism can shape the physical architecture of the brain. These revelations may help demystify the longstanding racial disparities in psychiatric disorders, such as PTSD.

The impact of societal disparities is shockingly evident even in children as young as 9 to 10 years old, where changes in brain development associated with trauma and stress-related disorders can be observed.

If we fail to acknowledge these disparities and continue to adopt a colorblind approach, Harnett warns, we risk developing mental health solutions that are not effective for all people.

The research underscores the grim reality that Black children in America disproportionately experience adversity due to deep-rooted and historical structural inequalities.

The study indicates that the caregivers of white children were thrice as likely to be employed and considerably more likely to have higher education levels and incomes exceeding $35,000. On the contrary, Black children were more frequently exposed to traumatic events, family conflict, and lived in poorer, more violent neighborhoods.

Linking such factors to subtle differences in brain development has been challenging, primarily due to small sample sizes in many brain imaging studies and a lack of diversity in research.

The current study surmounted these obstacles by leveraging the extensive Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study, established by the National Institutes of Health in 2015.

Although the ABCD study didn’t perfectly mirror the American population, it proved more diverse than most similar studies and included nearly 1,800 Black children.

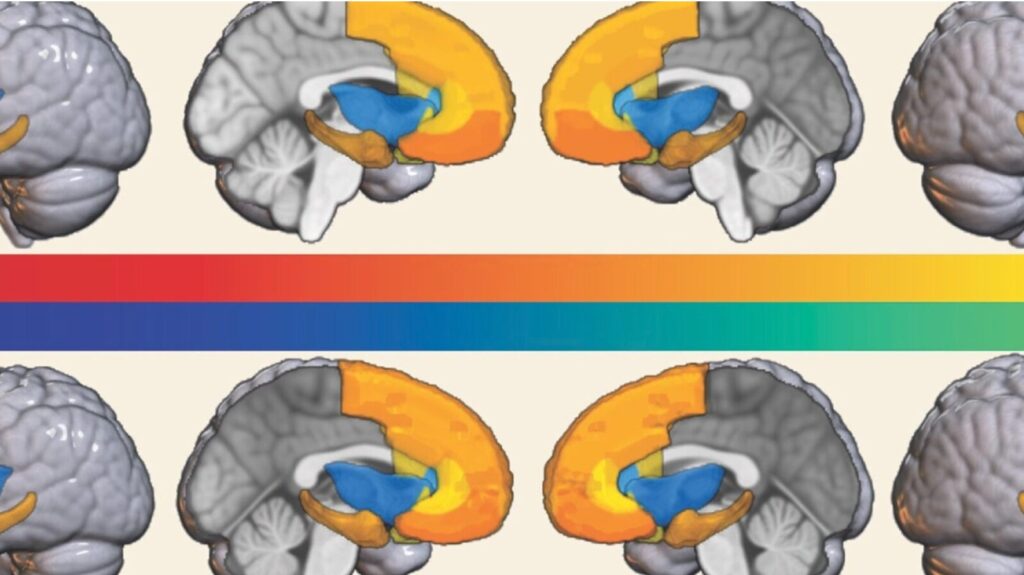

Harnett’s team discovered that Black children had a lower volume of gray matter in 11 of 14 examined brain areas. Gray matter is rich in neurons that process information, and such a reduction has previously been erroneously attributed to race.

However, modern scrutiny and overwhelming scientific evidence assert that race is a social construct, with all humans sharing 99.9% of their DNA regardless of racial categorization.

Upon analyzing the data, Harnett stressed, “This is not a race effect. It’s race-related. The adversity is related to structural differences.”

The experiences that we undergo shape our responses to future trauma, and these experiences often fall along racial lines.

The repercussions of this study extend beyond the realm of academia. Negar Fani, a neuroscience researcher at Emory University, stated that the findings are “a tremendous contribution to our understanding of how structural inequities evident in early development can create a pathway to increased risk for brain health disparities in Black Americans.”

It suggests that interventions designed to buffer against inequities and stress, such as training, therapy, or breathing exercises, should be tailored to specific racial and ethnic communities for increased effectiveness.

The study focused on three crucial brain areas: the amygdala, responsible for processing fearful and threatening stimuli; the hippocampus, which plays a significant role in learning and memory; and the prefrontal cortex, which regulates responses to fear.

These areas were found to be smaller in Black children and even more so in those who had experienced the most adversity. Notably, these children also exhibited more severe symptoms of PTSD.

Harnett interprets these findings as “the neuroanatomical consequences of racially disparate environments of toxic stress.”

Toxic stress can disrupt the architecture of the developing brain by causing an imbalance in neuron creation.

These alterations may not become evident until adulthood and may influence how the brain ages. Another recent study suggested that the brains of Black Americans might age faster due to the impact of racial stressors.

However, it’s essential to note what the researchers didn’t find or couldn’t include due to the study’s limitations.

Factors such as neighborhood-level pollution and family conflict were examined, but nutrition and direct exposure to toxins weren’t included. Harnett remains hopeful that these changes could be mitigated with nurturing and more resources.

Deanna Barch, a principal investigator with the ABCD study, voiced concern that the research, by attributing only some of the brain differences to social factors, might be misconstrued as implying that race could still play a part.

Images showing differences in gray matter volume between Black and white children (top) and showing the differences are less (bottom) when racial disparities in socioeconomic factors are taken into account.

DUMORNAY ET. AL., AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRY

She cautioned against naive or malicious interpretation of the results and stressed the likelihood of other social factors accounting for the brain differences, such as the direct effects of racism, school quality, and interactions between factors like family income, material hardship, and neighborhood safety.

This study is a clarion call to psychiatry, a field with a history of entrenched racism, to address wide disparities in mental health care access proactively. Ned H. Kalin, chair of the department of psychiatry at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, and editor-in-chief of the American Journal of Psychiatry, affirmed the critical importance of these findings.

He urged the field of psychiatry to be vocal about the detrimental psychological impacts of race-related disparities in childhood adversity and to fervently support efforts aimed at rectifying these disparities.

In conclusion, while the findings of this study highlight alarming disparities, they also shed light on potential pathways towards more equitable mental health outcomes.

By creating mental health solutions that acknowledge and address the harmful impacts of systemic racism and socioeconomic adversity, we can strive to build a future where all children, regardless of race, have the opportunity to grow, thrive, and reach their full potential.

Black Wall St. MediaContributor