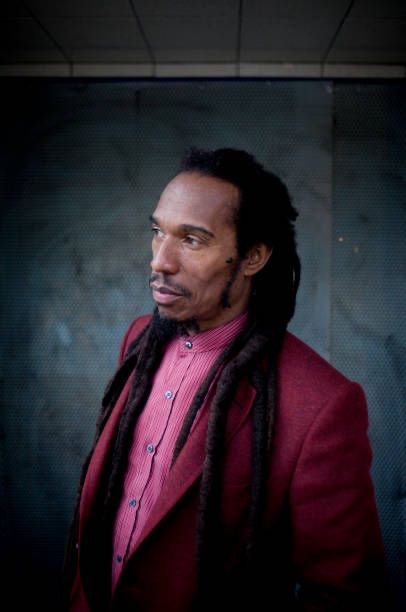

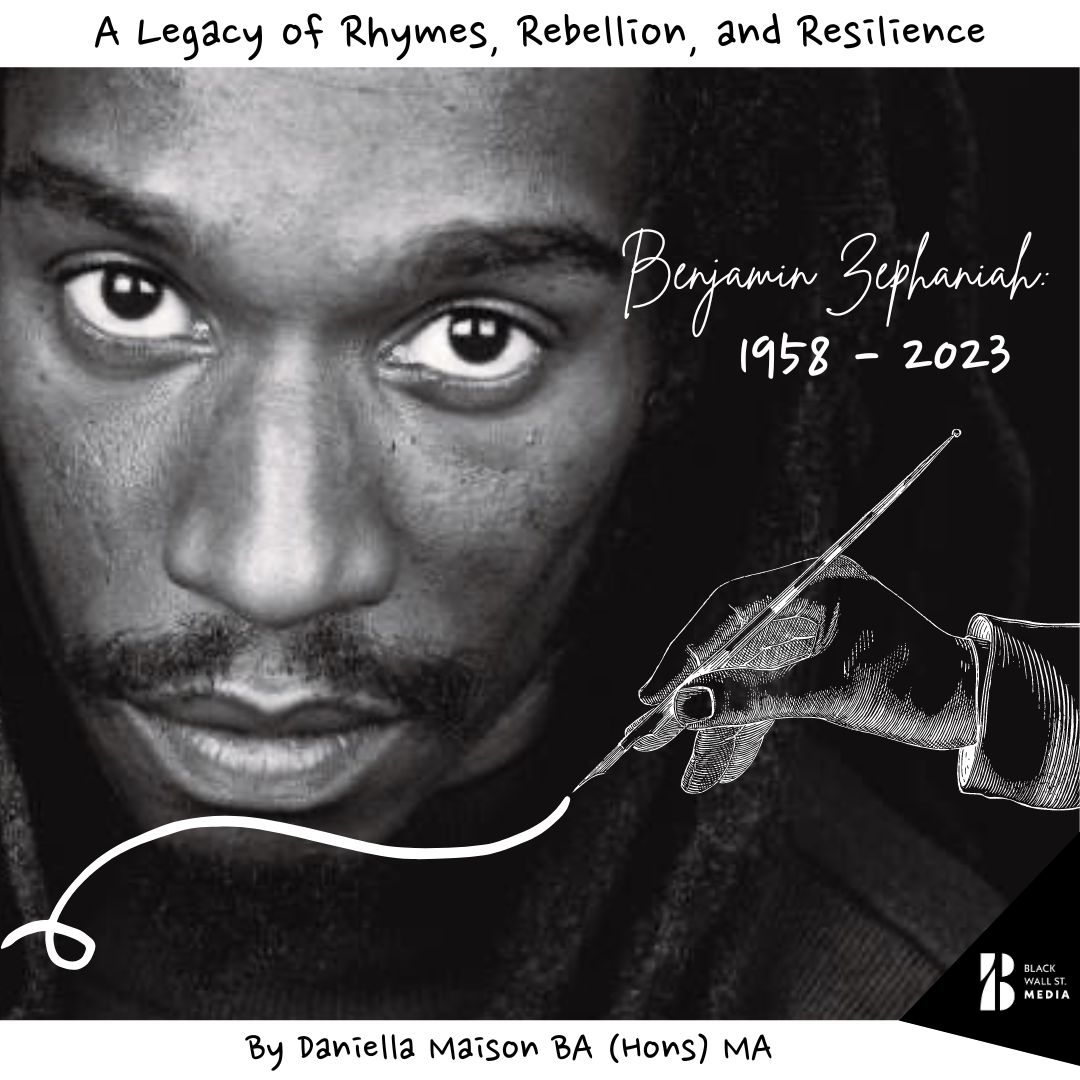

Tribute

Pen Rhythm Prince: Celebrating the Life and Works of Benjamin Zephaniah

“Remembering the incomparable Benjamin Zephaniah, a literary legend and rebel writer. His legacy of words, spoken in rhyme and revolution, continues to inspire generations. Join us in celebrating the enduring impact of a dyslexic genius, a Rasta revolutionary, and the People's Poet. Let the echoes of his soulful rhymes and unyielding vision resonate.”

Daniella Maison BA (Hons) MAEditor of Social Cause Issues

Remembering Benjamin Zephaniah: A Tribute to the Literary Titan

When I awoke to the news that the great Benjamin Zephaniah had died, I was desolate to have lost a personal creative influence and saddened that the world will never again hear the rebellious Brummie tone that expressed a beautiful mind. What is the literary word without the Pen Rhythm Poet? A hopeful morning went to rack and ruin.

The dreary December weather became a pathetic fallacy. My spirit was sent into a blue funk.

Eight weeks ago, Benjamin was diagnosed with a brain tumour from which he never recovered, and he died yesterday aged just 65.

Benjamin Obadiah Iqbal Zephaniah was born and raised in Birmingham, the son of a Barbadian postman and a Jamaican nurse. He was dyslexic and left school aged 13, unable to read or write. He became the poster child for dyslexia. As a candidate for Oxford’s poetry professorship, he was ideally placed to shatter the stereotypes surrounding dyslexia, saying,

‘Dyslexia is not a measure of intelligence: you may have a genius on your hands. Having dyslexia can make you creative.’ For Benjamin, that was the understatement of the century.

He was a child of domestic abuse and regularly admitted that growing up in a violent household led to him assuming that was the norm. He recalled: “I once asked a friend of mine, ‘What do you do when your dad beats your mum?’ And he went: ‘He doesn’t.’ “I said, ‘Ah, you come from one of those, like, feminist houses. So, what do you do when your mum beats your dad?’ This fusion of brutal candour and riotous humour was his trademark, and he executed it with natural aplomb.

Growing up in the midst of adversity gave Benjamin an endless compassion for others, especially children and teenagers. It also gave him a unique edge that he channeled through his writing with inimitable proficiency.

Beyond Rhymes: Benjamin Zephaniah’s Journey from Birmingham to the World

He moved to London aged 22 and published his first book, Pen Rhythm. His early work was original Dub Poetry, and he performed soul-stirring sets with the group The Benjamin Zephaniah Band.

As his profile grew, Benjamin became a familiar face on television and was credited with bringing Dub Poetry into British households. Today, when we enjoy the London spoken word scene, we are witnessing those who stand firmly upon his shoulders.

Benjamin wrote five novels as well as poetry for children, and his first book for younger readers, Talking Turkeys, was a huge success upon its publication in 1994.

His collection of work is outstanding. Benjamin was working in the field of diversity and inclusion before they were a commonplace cause. Books such as ‘We Are Britain’, are testimony to that.

My own love affair with poetry began as a child. It was the 1980’s and black literature and poetry was hard to find. So, I was blown away when my mother bought me a collection of Caribbean poetry to whet my budding creative appetite. Benjamins ode to his mother was the first poem in the book and my mother and I would recite the words to ‘I love me mudder’ together as though it was a song.

‘I love me mudder and me mudder love me

we come so far from over de sea

We heard dat de streets were paved with gold sometime it hot sometime it cold.’

That was 1986, and some 30 years later, my 5 year old nephew Theo pointed out a house in a book and said to his mum that it might be ‘Zephaniah’s house’. When his mum asked, ‘Who’s that?’ He said. ‘A poet, mum. We read him at school’.

I smiled. It was a small moment but a gargantuan testimony to the illimitable, amaranthine dynamism of Benjamin’s legacy. Yes, he cooked up his first works in the 70’s in the contentious backdrop of Thatchers Britain surrounded by National Front graffiti’d walls and ‘there ain’t no black in the Union Jack’ chants, and yet children in modern schools from all backgrounds, are still digging his work.

Beyond Rhymes: Benjamin Zephaniah’s Journey from Birmingham to the World

In my teens, my mother bought me a Rhyming Dictionary for which he had written the preface and not long after my first poem was published and my writing journey officially began.

At age 21, I was a bright eyed and aspiring young writer and soon to be university student, and I met Benjamin in Milton Keynes. He keenly but coolly impressed upon me the value and importance of writers ‘your pen is the instrument of your voice’. ‘I’ll mention you in my next article!’ he grinned. Weeks later, on beginning my degree, when he referenced me in a piece about his visit to Jamaica as ‘an Angel he met in Milton Keynes’, I was encouraged. My pen is the instrument of my voice, I reminded myself. My pen is the instrument of my voice.

In 2014, our paths crossed again when we lost a mutual loved one in tragic circumstances. I reminded him that it was me he had met in Milton Keynes some 12 years prior. ‘I am still writing, my brother.’ I declared. ‘I am working on a book’. I pray Moses, at his request, that I would send it to him once it was completed.

Benjamin was a powerful proponent of the proverb ‘one hand cannot clap’. Years later. I sent him a copy of my book, The N Word, and he sent me an outpouring of galvanising support. Several weeks later, in true Benjamin style, he sent me an apology that it had taken him ‘so long’ to read it. ‘I’m filming a drama, recording music, planting winter crops, and doing other creative things that are keeping me very busy’ he divulged.

Shortly after came his written endorsement for which he intended to be the foreword for my book. ‘I hope it is of some use to you’, he added unassumingly.

Benjamin described himself as a “poet”, and yet he was very much more. The Godfather of spoken word, he was a One Man Last Poet. He was a mentor and maestro, revolutionary, versifier, activist, disrupter and peace maker. Benjamin loved people with an enduring passion.

His great gift was that despite his indisputable effulgence he was never preacher or sermoniser. He never claimed to be our prophet or visionary. An ardent Aston Villa fan, a lover of martial arts, a Rasta and vegan, he was The People’s Poet. Regardless of how interstellar his name became, he remained so.

Sweet-natured, goodhearted and even-tempered, Benjamin possessed a warrior spirit that he unleashed unabashedly referring to himself as a ‘trouble maker’ when he needed to be.

His work speaks for itself on that front. In the early 80’s, Zephaniah released an album called Rasta, which featured the Wailers’ first recording since the death of Bob Marley.

It also included a tribute to the then-political prisoner Nelson Mandela, who would later, of course, become South African president.

Famously, Benjamin once rejected a royal honour, refusing to have the word ‘empire’ associated with his name in any conceivable way. ‘Me? I thought, OBE me? Up yours, I thought. I get angry when I hear that word “empire”; it reminds me of slavery, it reminds of thousands of years of brutality, it reminds me of how my foremothers were raped and my forefathers brutalised.’

When Benjamin said he believed in something, he was marvellously sincere. Commitment and words were never meaningless or throwaway; he was unwavering in his commitment; a dyed-in-the-wool true blue to the cause. Still, his message was never divisive, it remained unwaveringly one of unity, peace and expression.

My favourite recording of Benjamin is of Benjamin in Brixton at what was then Ye Olde White Horse pub (and is now Brixton Jamm), in 1983. Margaret Thatcher, Conservative Prime Minister had won a landslide victory in the general election and the country was in discord.

Before an almost-all-white crowd, Benjamin stepped forward and declared ‘Now look at me I’m a Afrikan, I walk with a Afrikan tread. Feel no way I’m a Afrikan, I think with an Afrikan head’ to a silent room with charismatic fervour.

At a time when we pride ourselves on our freedom to speak and express freely, it’s hard to imagine the sheer chutzpah that took, not knowing what the reaction would be. These recordings are creative gold dust now. Of course the rest is history as some 40 years since that night he is rightfully considered, and hailed as, a Titan of global literature.

A Titan indeed. With a heavy heart I put my pen to paper to say that one of the most brilliant minds of our times is gone for now, but his voice will be extinguished never. His rhymes will echo in the ether. His ink will never dry.

Benjamin never sent a message to me without signing it off ‘All The Love’.

”All The Love, Benji, our shining Pen Rhythm Prince. God Speed.

Black Wall St. MediaContributor