HISTORY

The Mandingo Muslims Of Trinidad

“Diving deep into the captivating tale of Muhammad Sisei, this article unveils the journey of a Mandingo Muslim from the heart of Gambia to the shores of Trinidad, marking his legacy amidst the tumultuous trans-Atlantic slave trade era. As we celebrate #BlackHistoryMonth, let's rediscover and honor these forgotten stories that shaped the fabric of our shared history.”

Black Wall St. MediaContributor

The Mandingo Muslims Of Trinidad

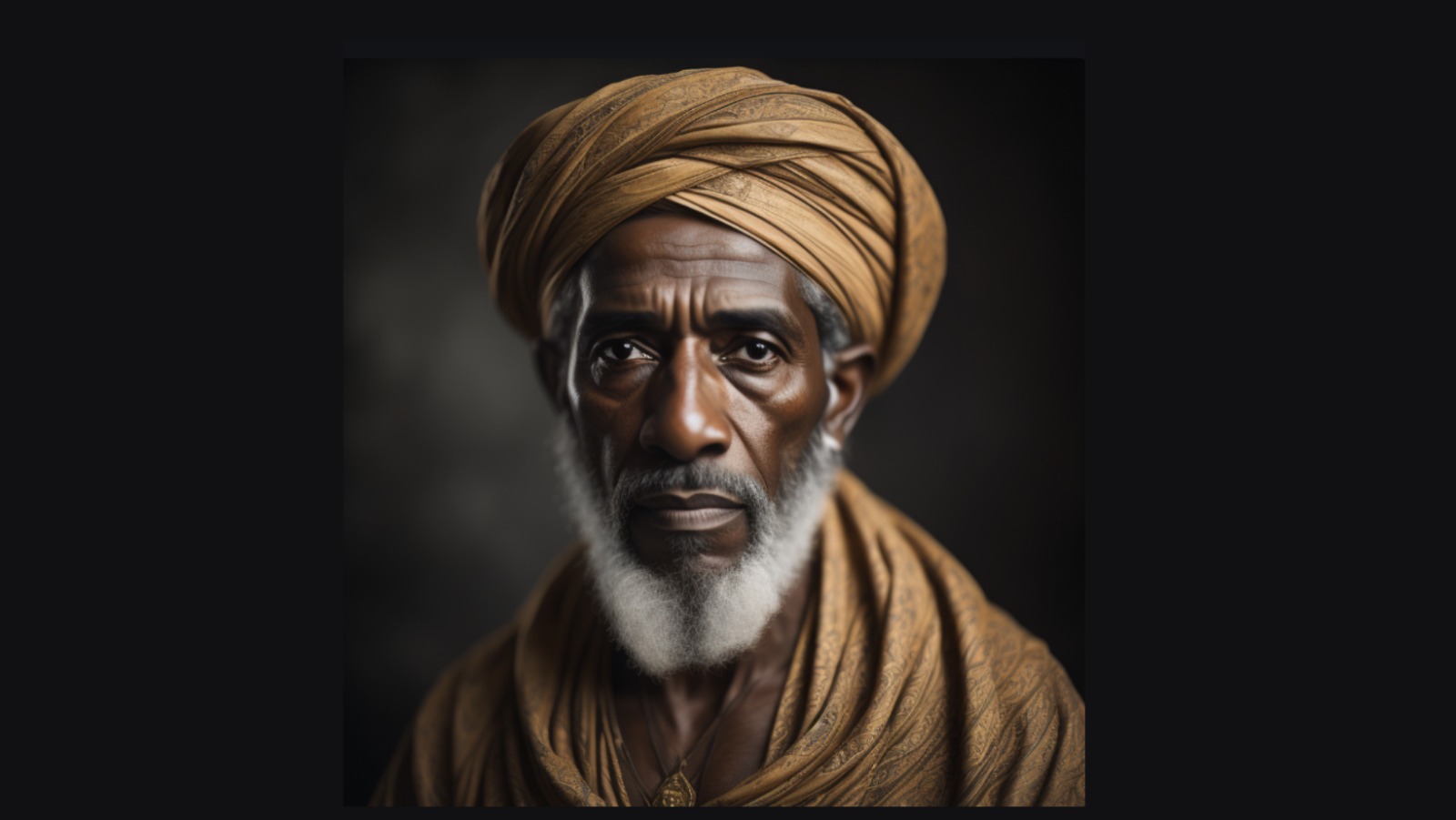

Yunus (Jonas) Muhammad Bath

Muhammad Sisei (1788 – 1838): Tracing Roots from Manding Muslim Civilization

The tale you’re about to read intertwines with the extensive Manding Muslim civilization that flourished in West Africa for three centuries, extending from the regions beyond Timbuctu to the Atlantic coastlines.

This narrative casts light on the reason why even today, Muslims in Trinidad are referred to as ‘Madingas’.

It’s widely acknowledged that the initial Muslims to set foot in Trinidad hailed from West Africa. However, intricate details about their practices and the depth of their Islamic observance remain scant. Given the oppressive nature of the European slave plantation system, many were either compelled to secretly maintain their religious practices or completely abandon them.

A clearer understanding emerges when parallels are drawn to slave experiences in other West Indian islands and the Americas, as illustrated vividly in “ROOTS” by the renowned American author, Alex Haley.

The chronicle of these pioneering Muslims in Trinidad remains largely shrouded in mystery. What follows is an attempt to shed light on this overlooked chapter, primarily deriving insights from Carl Campbell’s research, as published in the African Studies Association of the West Indies’ journal.

By the dawn of the 19th century, a vibrant Muslim community had established its presence in Port of Spain, led by the prominent Yunus (Jonas) Muhammad Bath.

Their community saw an influx of African members who had formerly served in the British West Indian Regiment during the Napoleonic wars.

Post their military service, some found homes in Port of Spain, others ventured south to Trinidad, but a significant portion were granted lands in Manzanilla, situated in Trinidad’s northeast.

At least those who settled in Port of Spain made pleas to the British administration for a return to Africa, though their appeals went unheeded.

However, one individual’s relentless pursuit did see him retracing his steps back to Africa, via England. His captivating journey belongs to none other than Muhammad Sisei.

Muhammad Sisei, believed to have been born between 1788 and 1790, hailed from the Gambia and was a proud member of the Mandingo tribe. During that era, the majority of the Mandingo population were likely adherents to Islam.

Deeply rooted in Islamic heritage, his father was named Abu Bakr, echoing the legacy of Prophet Muhammad’s first successor, and his mother bore the name Ayishah, reminiscent of the Prophet’s beloved wife.

Originating from Niyani-Maru, a village nestled on the northern curve of the Gambia river about 100 miles from the Atlantic’s embrace, young Sisei embarked on his religious journey at eight.

He was sent to Dar Salami (Dasilami), recognized as a pivotal hub for Islamic education in the Gambia.

With the Gambia dotted with such educational centers, primarily established by Muslim merchants on their trade expeditions across West Africa, it illuminated one of the primary channels through which Islam flourished in the region.

Under the guidance of Dar Salami’s educators, Sisei immersed himself in the Arabic script and delved deep into the teachings of the Qur’an.

The institution highly valued written knowledge, a reflection of Islam’s monumental contribution to global literacy, particularly in Africa.

Post an eight-year rigorous educational stint at Dar Salami, Sisei, now around sixteen, found his way back to Niyani-Maru in approximately 1804.

His subsequent years saw him chart various journeys, notably a maritime venture in 1805 from his hometown, which served as a prominent port, to the French-held Goree. Driven by trade ambitions and potentially to gather gifts for his soon-to-be wife, Aiseta, a relative, this voyage stands out.

Settling into matrimonial life, Sisei established a school in his hometown, translating his learnings from Dar Salami into teachings, thus fostering and strengthening Islam’s footprint in the vicinity.

However, the early 19th century in West Africa, particularly the Gambia, was marked by turbulence. Amidst the backdrop of the Anglo-French contention, local chieftains waged wars for dominance. Sisei’s tranquil existence as an educator was disrupted by these conflicts. Amid one such strife where chiefs vied for the banks of the Gambia river, disaster struck Sisei’s hometown. Subsequent to a clash, the retreating chief regrouped and launched a successful assault on Niyani-Maru, ensnaring Muhammad Sisei in the process.

After enduring captivity in Kansala for five strenuous months, Sisei was then forcibly relocated to the coastal town of Sikkah. Here, in a cruel twist of fate, he was traded to a French slaver, whisking him away from his homeland.

Merely five days after departing from Sikkah aboard the French slaver, the ship was intercepted by a British naval frigate. This intervention was part of Britain’s efforts to enforce the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade, a decree it had officially put into place in 1807.

Upon this encounter, Sisei was brought aboard the British vessel and subsequently taken to Antigua. In a fortunate turn of events, Sisei was spared the harrowing experience of plantation slavery. The rationale behind this decision was the complexities associated with integrating free Africans into Antigua’s tightly-knit slave community.

Swiftly transitioning to his new circumstances, Sisei was enlisted into the Third West India Regiment, taking on the role of a grenadier. The British renamed him Felix Ditt during this phase.

Initially, black regiments like these were meant to serve exclusively within the West Indies. However, as part of the regiment, Sisei, now recognized as one of the “Kingsmen” – a term distinguishing him from enslaved individuals – was actively deployed against the French in Guadeloupe and had even been stationed in Barbados at one point.

From 1811 to 1825, Sisei, a Mandingo Muslim, stood side by side with fellow African soldiers from diverse ethnic backgrounds such as the Yoruba, Ashanti, Foulah, Susu, and Hausa. Among these, the Foulah, Susu, and Hausa groups likely had members who practiced Islam, much like Sisei.

Sisei’s primary residence in the West Indies was Trinidad. He landed there in 1816, and by 1825, he was honorably discharged from the Regiment due to his commendable conduct.

While many of his counterparts were allocated land in the Manzanilla district of Trinidad, a location distant from the west coast’s slave plantations, Sisei neither received nor accepted any land or pension.

Instead, he relocated to Port of Spain, integrating into the Muslim community under the leadership of Yunus Muhammad Bath.

Yunus Muhammad Bath was a charismatic figure, spearheading a Mandingo Muslim enclave within Port of Spain.

This community diligently practiced Islam and collectively sought to gather funds to liberate Muslim slaves.

Although some achieved financial success, they yearned for a return to Africa, petitioning the British government thrice with requests for repatriation.

A particular petition, addressed to King William IV of Great Britain and Ireland, commenced with the Arabic salutation, “Allahuma Sally alla Mahomed” — Oh God, bless Muhammad. Nonetheless, their pleas went unanswered, compelling these Mandingo Muslims to permanently settle in Trinidad.

Yet, for Sisei, a return to Africa was paramount.

Leveraging funds borrowed from a fellow Muslim, he secured passage to England for himself, his Grenadian creole wife (whom he had married in 1831), and their child.

Arriving around 1938, Sisei found an ally in John Washington, the Royal Geographical Society’s secretary.

Washington, intrigued by Sisei’s knowledge of West African languages and geography, believed that Sisei could be instrumental in British expeditions into Africa’s heartland.

Thanks to Washington, a key chronicler of Sisei’s life, we gain insight into Sisei’s character.

This dedicated Muslim was described as bright, astute, and deeply committed to his faith.

He possessed extensive knowledge of the Qur’an, always keeping certain parts of the sacred text close to him.

Sisei showcased his proficiency in Mandingo by writing in Arabic characters, a testament to the widespread intelligence often associated with the Mandingoes by travelers of that era.

Eventually, Muhammad Sisei departed England to return to Gambia. Given the ease with which one could access his birthplace, Niyani-Maru, by boat, it’s plausible to believe that Muhammad Sisei, also known as Felix Ditt, made his way back to his roots.

Muhammad Sisei’s tale stands out as a poignant chapter in the chronicles of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Numerous compelling stories akin to Sisei’s have been unearthed and narrated, though with varying depths. One such account is “The Fortunate Slave” by Douglas Grant, published in 1968 by Oxford University Press. This narrative delves into the life of Ayyub ibn Sulayman (Job ben Solomon), a Fulani amir’s son captured and transported to America in the 1730s.

There’s no doubt that countless individual stories parallel to Muhammad Sisei’s exist, offering a treasure trove of insights for those seeking to delve deeper. In the Trinidadian backdrop, the fate of Muslim communities in Port of Spain, Manzanilla, and South Trinidad remains an enticing topic warranting further historical exploration.

Sources:

-

Alex Haley’s quest into his lineage unveiled a Muslim heritage. His ancestor’s village, Juffore in Gambia – from where he was enslaved – has, according to Haley, always been a Muslim stronghold. In tribute, he erected and dedicated a mosque in Juffore.

-

“Slavery Days in Trinidad” by C R Ottley, Trinidad, 1974

-

“Mohammedu Sisei of Gambia and Trinidad c. 1788-1838” in Bulletin of the African Studies Association of the West Indies, No. 7 by Carl Campbell.

Originally featured in The Muslim Standard’s (Trinidad) April 1977 issue.

(BELOW) A portrait of Ayuba Suleiman Diallo

(BELOW) Two young Mandinkas

Black Wall St. MediaContributor