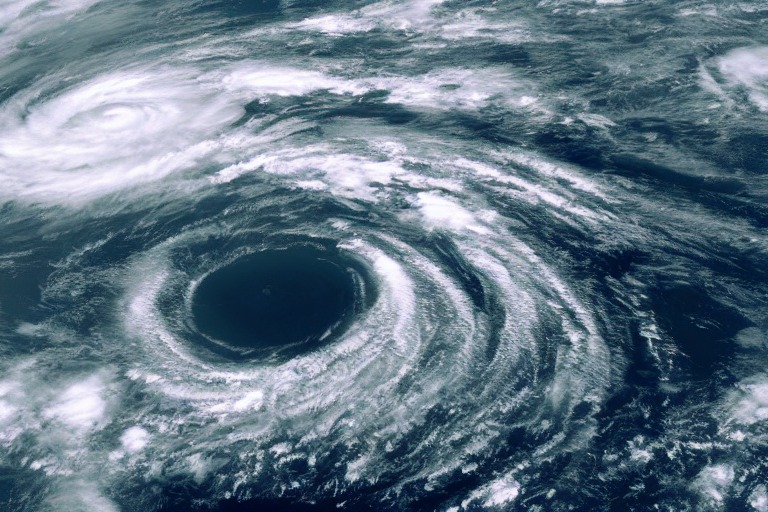

The Caribbean region is perhaps the most severely threatened by climate change, particularly as it is primarily composed of island nations, making climate change an existential crisis.

Unless significant efforts are made by larger nations to reduce global warming, the region faces a bleak future.

Unless significant efforts are made by larger nations to reduce global warming, the region faces a bleak future.

Estimates indicate that by 2050, the Caribbean could face an annual cost of up to USD $22 billion due to damages from hurricanes, loss of tourism, and infrastructure damage if no action is taken.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicts that without intervention, some small island nations may become uninhabitable this century, leading to large-scale migration.

As a result of the warming climate, people in the Caribbean region are already being forced to move. In 2017, nearly 2 million individuals were internally displaced due to a particularly damaging hurricane season, according to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Center.

Even conservative estimates from the World Bank suggest that by 2050, approximately 216 million people from impoverished and climate-vulnerable regions will be displaced as a result of both slow-onset events and sudden-onset natural disasters related to climate change.

Small Island Developing States (SIDS) are faced with multiple natural hazards and limited financial resources, which hinder their capacity to build resilience and develop adaptation strategies.

This makes them more vulnerable compared to other regions. The Caribbean region is already experiencing the negative impacts of sea level rise, intense tropical cyclones, storm surge, saltwater intrusion, droughts, changing precipitation patterns, and coral bleaching, which are degrading terrestrial and marine ecosystems, exacerbating food and water insecurity, and putting a strain on regional economies and critical infrastructure.

In fact, according to the 2021 Global Climate Risk Index, Puerto Rico (1), Haiti (3), and the Bahamas (6) are among the ten countries and territories that have been most affected by extreme weather events over the past two decades.

Despite establishing a significant network of agreements on migration and disaster risk management, the progress in the Caribbean region has been significantly hindered by challenges like the impact of COVID-19.

The region’s long-standing economic and financial constraints are also preventing the implementation of much-needed measures to mitigate, adapt, and build resilience to potential large-scale migration events. Furthermore, crimes associated with migration are on the rise as more people move, particularly through illegal channels, which exposes migrants to severe human rights violations such as forced labor, criminal recruitment, and sexual abuse.

The absence of regular migratory pathways and poor state control over borders have further exacerbated this problem.

Although the 2018 Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM) acknowledges that climate change is influencing migration patterns, there is currently no agreed-upon definition or international legal framework that provides protection to people moving due to or in the context of climate change.

This is a technically complex and politically sensitive issue.

For instance, someone fleeing Haiti’s security and economic crises may be classified as a refugee or economic migrant, rather than an environmental migrant or climate refugee, despite facing concurrent climate-related challenges.

The movement of Bahamians or Dominicans (from Dominica) to Trinidad and Tobago, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, or the United States is an example of this.

Did hurricanes Dorian and Maria destroy their homes? What about the approximately 129,000 Puerto Ricans who fled to the Continental United States in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria or the rural Dominicans who are migrating to Santo Domingo as the effects of climate change devastate their livelihoods? Do all these individuals fall under the same classification?

Environmental migrant, climate migrant, and climate refugee are just a few of the many terms used to describe this group.

However, these terms are frequently ill-defined and used interchangeably, despite their distinct legal and political implications. So, what distinguishes environmental migrants from climate migrants and climate refugees?

Despite the differences and complexities, we believe that defining “climate migration” is important since it underscores the unique challenge that climate change poses to the Caribbean and acknowledges the interrelated nature of the causes of human movement.

Unlike the term “climate refugee,” which implies a specific legal status, “climate migrant”—first introduced by the International Organisation for Migration—recognises the various types of population movements linked to climate change, as well as the corresponding and interrelated drivers of migration.

The Caribbean has a multi-causal relationship between human mobility that includes political, economic, social factors, and natural hazards, which further entangle the nexus between climate change and migration.

The adoption of a term that acknowledges the overlapping nature of these relationships will help policymakers better understand and develop policies that address this phenomenon, which will only exacerbate in the future.

While climate migration is primarily an internal process, several studies indicate a growing trend of cross-border movements. Recent research has linked slow-onset environmental degradation processes with international migration in both Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

Similarly, the impact of hurricanes and tropical storms in the Caribbean has been linked to an increase in regular migration to the United States. As a result, new international, regional, and national frameworks will be necessary to regulate human movement and provide protection. Failure to establish a clear definition and legal framework will only complicate an already complex issue.

Cooperation and coordination among Caribbean nations, the United States (currently the main destination for Caribbean migrants), regional organizations, international institutions, development agencies, and lawmakers are essential to developing migration policies that address the complex challenges posed by human mobility.

Crafting such policies will require innovative and thoughtful solutions, but will inevitably involve politically sensitive issues, including admission numbers, allocation of resources, and citizen security.

Recognizing the urgent need for updated multilateral immigration policies that account for the impact of climate change is crucial. Moreover, this will require large economies such as the United States, European Union, and China to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions.

However, effective policy strategies must also include prevention and planning measures and explore various governance options for Caribbean nations and their partners.

For more information and recommendations as well as an analysis of the impacts of climate change on the Caribbean’s indigenous and tribal peoples, read the full report.