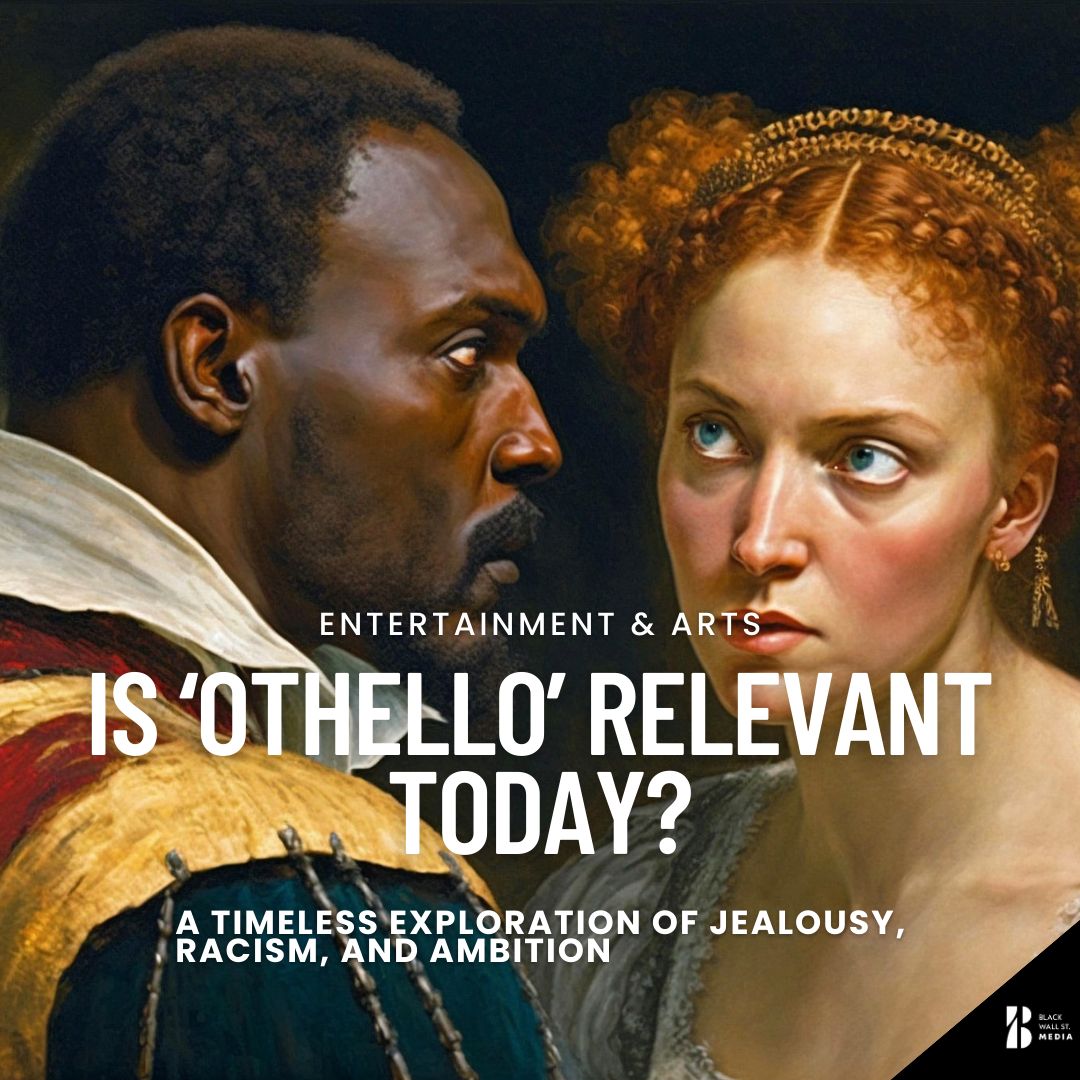

Othello: A Timeless Exploration of Jealousy, Racism, and Ambition

Is ‘Othello’ relevant today?

Written over four centuries ago, it continues to be performed and studied today, a testament to its timeless themes and enduring relevance.

At its core, Othello is a play about human nature and the destructive consequences of jealousy, racism, and ambition.

The story follows the tragic downfall of the eponymous protagonist, a noble black general in the Venetian army, who becomes the victim of a vicious plot orchestrated by his envious and deceitful subordinate, Iago.

The play’s exploration of jealousy and its corrosive effects on relationships is particularly relevant in today’s society.

In the age of social media, where envy and jealousy can be easily amplified and weaponized, the play’s message about the destructive power of these emotions is more pertinent than ever.

Through the character of Othello, Shakespeare portrays the dangers of allowing jealousy to consume us.

Othello’s initial love and trust for his wife, Desdemona, are destroyed by Iago’s lies and manipulation, leading to his eventual downfall.

The play is a warning against the dangers of letting our emotions control our actions, and a reminder of the importance of communication and trust in any relationship.

Another key theme explored in Othello is racism and prejudice.

Othello’s status as a black man in a predominantly white society makes him a target for discrimination and prejudice. The play exposes the insidious nature of racism and the harm it can cause, both to the individual and to society as a whole.

It also highlights the importance of empathy and understanding, and the need to confront and challenge prejudice whenever we encounter it.

Finally, the play also examines the destructive nature of ambition and how it can lead to our downfall.

Both Othello and Iago are driven by their desire for power and recognition, and their ruthless pursuit of their goals ultimately leads to tragedy. The play serves as a reminder of the importance of humility and the dangers of unchecked ambition, a lesson that is just as relevant today as it was in Shakespeare’s time.

In conclusion, Othello is a timeless masterpiece that continues to resonate with audiences today. Its exploration of jealousy, racism, and ambition speaks to some of the most pressing issues of our time, reminding us of the importance of communication, empathy, and self-awareness.

Overall, Othello’s enduring relevance lies in its ability to hold up a mirror to contemporary society and to provoke discussion and reflection on some of the most important issues of our time.

As we continue to grapple with these challenges, the play serves as a powerful reminder of the dangers of allowing our emotions to control us, and the importance of striving for understanding and compassion in all our interactions.

Black Wall St. MediaContributor